Introduction

In response to dwindling electoral support for many social democratic parties in Western Europe, various strategies have been suggested to bring social democratic parties back on the winning track. One particularly persistent recommendation, prevalent since at least 2019, dominates public discourse and media coverage regarding the Left’s strategic direction: adopting welfare chauvinism. Welfare chauvinism refers to an ideological stance that principally supports redistribution and a generous welfare state for “deserving” country nationals while aiming to curtail immigrants’ access to these benefits (Careja and Harris 2022). The term welfare chauvinism originated from Andersen and Bjørklund (1990: 212) to describe the views of Scandinavian right-wing populist party voters that “welfare services should be restricted to our (country’s) own”. It has since become a core element in the economic agenda of right-wing populist parties but has gained traction also beyond the right. Notably, the Danish Social Democrats, led by Mette Frederiksen, incorporated welfare chauvinist components into their immigration policies. These policies included supporting and, when in power, implementing measures such as withholding government benefits from immigrants who refused to enroll their children in Danish values and language courses, limiting access to social housing for non-westerners in specific neighborhoods, and obliging certain migrant groups to work 37 hours a week to qualify for welfare benefits.

The Danish Social Democratic Party’s shift toward welfare chauvinism has not only sparked sharp criticism within segments of the European Left but has also received acclaim. In Germany, for example, influential figures like former SPD party leader Sigmar Gabriel have urged their parties to align themselves with Danish Social Democrats’ strategy to counter the trend of declining electoral support (Gabriel 2019). Similarly, numerous media commentators have extolled the Danish model as a potential blueprint for other Western European social democratic or radical left parties. It has been portrayed as capable of keeping in check the vote share of right-wing populist parties, winning (back) votes from these parties, and regaining the favor of the white working class, a group that has ceased to be a core constituency of many left parties (see the Research Briefs “A progressive service-class coalition?” by M. Ares and “The myth of vote losses to the radical right” by Tarik Abou-Chadi, Daniel Bischof, Thomas Kurer, and Markus Wagner).

However, when we consider recent political science research on the contemporary composition of left electorates, which is increasingly characterized by highly educated middle-class voters, and their motives to vote left, including their advocacy for marginalized societal groups, the electoral potential of a welfare chauvinist strategy becomes dubious (see the Research Brief “The myth of a divided Left” by Tarik Abou-Chadi and Silja Häusermann). Our research brief demonstrates that welfare chauvinism lacks significant backing among the current as well as potential voters of green, social democratic or radical left parties. By “potential voters” we mean those who in their survey answer indicate that they can well imagine voting for any of these parties but have actually given their vote to a different party in the last election. Moreover, substantial parts of current left voters could be expected to turn away from a party that outspokenly adopts welfare chauvinist stances. Consequently, the empirical evidence challenges the notion that emulating the welfare chauvinist stance of the Danish Social Democrats is a viable blueprint for the majority of other left-wing parties seeking to regain their former electoral prowess.

What speaks against welfare chauvinism being a winning strategy for the Left?

When welfare chauvinism is depicted as a winning strategy for the Left, this strategy is mostly thought to attract or reclaim the support of the traditional white working class, which currently votes disproportionally for right-wing populist parties. Advocates of this strategy frequently invoke a narrative coined by right-wing populist parties, suggesting that immigration into generous welfare states inevitably leads to benefit competition between immigrant and native-born welfare recipients (see for example statements by Sarah Wagenknecht (Trimborn 2023) echoing these sentiments). The underlying idea is that welfare chauvinism should prevent low-income, working-class country nationals feeling like they do not get their fair share. Indeed, research shows that welfare chauvinism resonates more strongly with low-educated, low-income working-class voters than with other groups (Harris and Enggist 2024). However, deducing from this that welfare chauvinism is an electorally successful strategy for the Left overestimates the electoral importance of this traditional working-class constituency and downplays the importance of other voter demographics for left parties.

Arguments in favor of welfare chauvinism as a winning strategy for the Left often overlook the current composition of left electorates and what motivates their vote choices. Electorates of especially green but also social democratic and radical left parties in Western Europe have become increasingly highly educated and middle class over the last five decades (Harris and Enggist 2024, Gingrich and Häusermann 2015). Notably, socio-cultural professionals, that is highly educated individuals working in occupations characterized by interpersonal work logic – such as teachers, social workers or doctors – have replaced the traditional working class as the core constituency of the Left (Oesch and Rennwald 2018).

This new middle class supports the Left not only for their stances on redistribution and welfare, as they might not benefit directly from these due to their socio-economic status. Instead, their support is rooted in the Left’s progressive positions on environmental issues, gender equality and not least migration. Many middle-class voters support the Left exactly because they want individuals to be treated equally, regardless of their origin or lifestyle choices, and because they endorse assistance for structurally disadvantaged groups (Häusermann and Kriesi 2015; Abou-Chadi et al. 2023). The concept of welfare chauvinism directly contradicts these intentions many left middle-class voters have. Welfare chauvinism then can only be a successful strategy for left parties if either these progressive, immigrant-friendly current left voters cared not enough about their party adopting welfare chauvinist stances to make them turn their back on their party. Or the potential of winnable (working-class) voters would need to be big enough to offset the (middle-class) losses of a left party to other left-liberal parties.

The potential of gaining as many new voters through welfare chauvinism as proponents of left welfare chauvinism expect is doubtful for two reasons. First, the decline in working-class representation within left electorates has its roots not only in an electoral realignment and parties’ position shifts. It is primarily due to broader structural transformations, including educational expansion, deindustrialization and automation. Due to these processes, the traditional working class in the production sector has been shrinking and the middle class enlarging not only in social democratic electorates but in West European societies more generally. Although some traditional working-class voters may hold welfare chauvinist views, their overall share has dwindled significantly compared to the 20th century, thereby diminishing their electoral relevance for left parties. Second, research on voting behavior shows that vote switching between left and radical right parties is a relatively rare phenomenon in most countries. Such shifts occur less frequently than vote switching within the Left or between left and mainstream right parties. Related to that, the pool of right-wing populist voters who might consider voting for a left party is relatively small (Häusermann 2023). It is questionable whether individuals who currently hold strong aversions to left parties, could be easily swayed to support the Left by copying the radical right’s welfare chauvinist original.

In the remainder of this research brief, we empirically check what left electorates think about welfare chauvinist proposals, whether attitudes differ between potential and existing left voters and whether existing left voters dislike welfare chauvinism enough so they might abandon their parties in response to the adoption of such stances.

Do current left voters support welfare chauvinism?

What do current left voters think about welfare chauvinist policy proposals? To address this question, we use data from a public opinion survey conducted during the winter of 2018/2019 in eight Western European countries (Germany, Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, UK, Ireland, Italy, Spain). This survey centered around understanding individuals’ welfare preferences, included various ways to gauge respondents’ perspectives on welfare chauvinism.

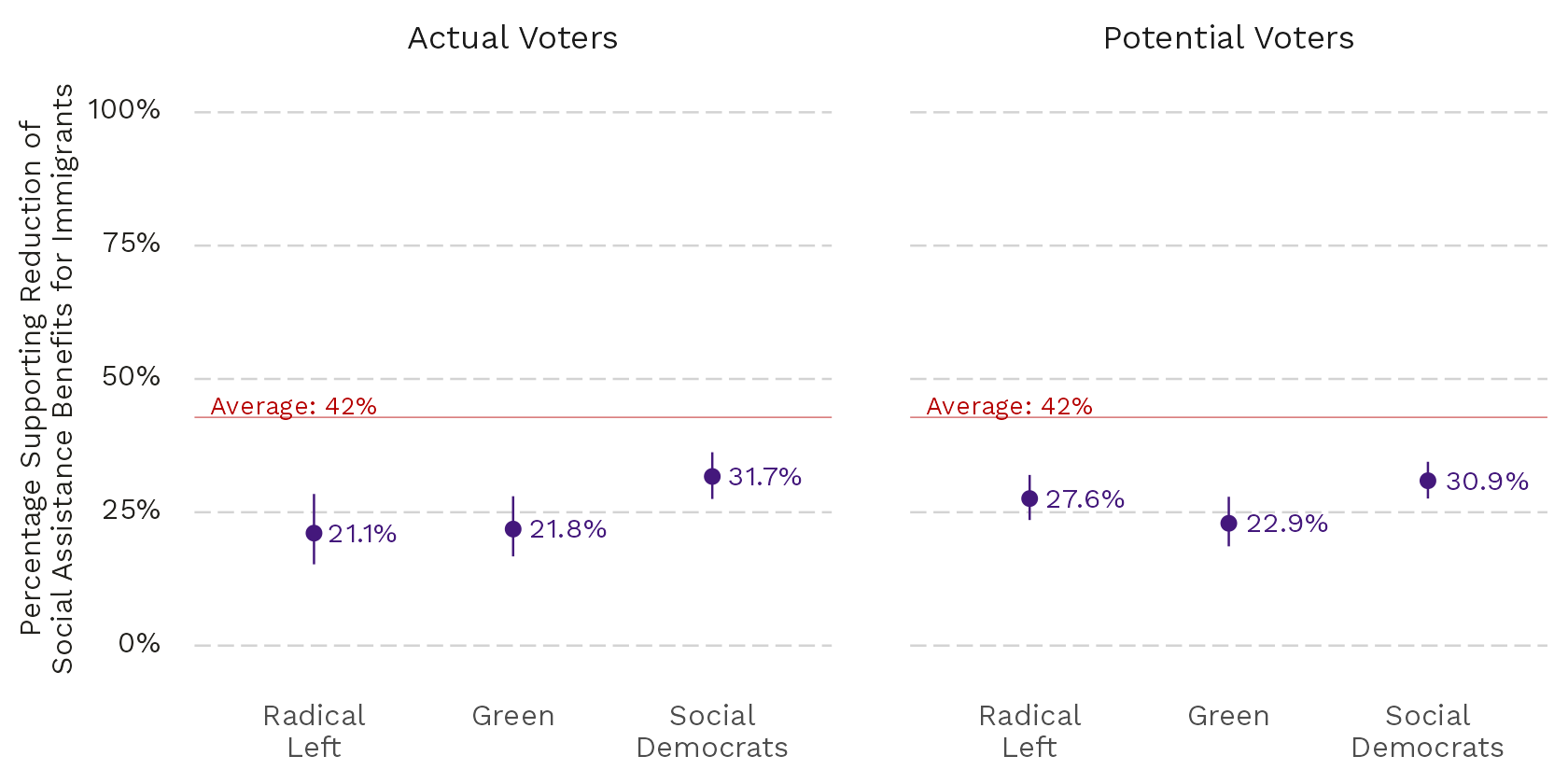

Figure 1 aggregates across all eight countries the percentage of voters by party family who agree or strongly agree with the statement that “the government should reduce social assistance benefits only for immigrants” (see also Enggist and Häusermann 2024). The dashed line indicates that across all voters in the eight countries 42% support reducing social assistance benefits for immigrants. Voters from all left party families are predominantly opposed to this policy proposal. It is supported by only 22% of Green, 28% of radical left and 29% of social democratic voters. This support is well below that of mainstream right voters (who are about as divided on this issue as European publics in general) and nowhere near that of radical right voters, who are strongly in favor of cutting welfare on the backs of immigrants. Looking at specific parties rather than party families, we observe no left party electorate, where a majority supports reducing immigrants’ benefits. This proposal is most supported by voters of the Irish Sinn Féin (44%), the Danish Social Democrats (38%) and the British Labour Party (36%) but least among the Irish Labour Party (15%), the Italian Partito Democratico (17%) and the Spanish Podemos (18%).

Figure 1: Share of party family electorate supporting the reduction of social assistance benefits exclusively for immigrants.

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto — Data source: survey conducted

Welfare chauvinism tends to receive more support when it takes the form of welfare expansion for country citizens rather than cutbacks for immigrants. The policy proposal to “expand social assistance benefits for country nationals only” receives support by 62% of people in the eight countries surveyed. Although this reform proposal entails an expansion of social assistance benefits for large parts of the population – which can be expected to appeal much more to left than to right voters – the pattern seen in Figure 1 largely holds. This lopsided social assistance expansion, which discriminates against immigrants, attracts no clear majority among voters of any left party family either and receives less support from left voters than from conservative, radical right or the average voter. Based on this evidence, welfare chauvinism does not look like a clear winning strategy for the Left.

Proponents of left welfare chauvinism might raise two objections as to why only lukewarm support for welfare chauvinism among current left voters does not preclude welfare chauvinism as an electoral winning strategy. First, while welfare chauvinism does not necessarily appeal to current voters, it might be a promising strategy for attracting voters from other parties, especially from right-wing populist parties. Second, it matters who cares about welfare chauvinism. If its proponents care a lot about welfare chauvinism whereas its opponents do not care a lot about defending immigrants’ rights, then welfare chauvinism could be a winning strategy even if it is supported by only a minority of left voters. We go on to test whether these two suppositions hold up to empirical scrutiny.

Does welfare chauvinism appeal to potential left voters?

In a follow-up survey in Summer 2020, which we conducted in three countries (Germany, Sweden and Spain), we ask the same questions, again capturing welfare chauvinist preferences, but also asking respondents to rate how probable it is that they will ever vote for certain parties on a scale from 0 (not at all probable) to 10 (very probable). This allows us to identify not only current party voters but also voters who have considered voting for a party but then decided against it. It is the preferences of these voters that we should focus on when assessing whether a party’s electoral strategy to attract new voters can be successful. We define respondents who give a score of six or more to this question as potential voters for a party. In contrast, a person who says it is unlikely that he or she will ever vote for a party, is relatively unlikely to switch to that party, even if the party changes its position on an issue that is important to the individual.

Figure 2: Share of actual and potential voters of left party family supporting the reduction of social assistance benefits exclusively for immigrants.

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto — Data source: survey conducted

Figure 2 shows that in all left party families the differences between actual voters and potential voters (i.e. all those who could imagine voting for the party) are remarkably small. For the Greens and Social Democrats, the difference in attitudes between actual and potential voters is negligible. For radical left parties, support for reducing immigrants’ welfare rights is only slightly higher among potential voters (29%). Winnable voters are also no more favorable than actual left voters to extending social assistance benefits to nationals only.

This may be partly due to the fact that we do not observe potential voters for left parties to be strongly working class. The working class is not over-represented among those who could be persuaded to vote for social democratic, green or radical left parties but currently do not. Thus, these results do not suggest that people who consider voting for left parties but abstain or vote for other parties are significantly more welfare chauvinist than those who currently for the left.

Who cares, and how strongly, about welfare chauvinism?

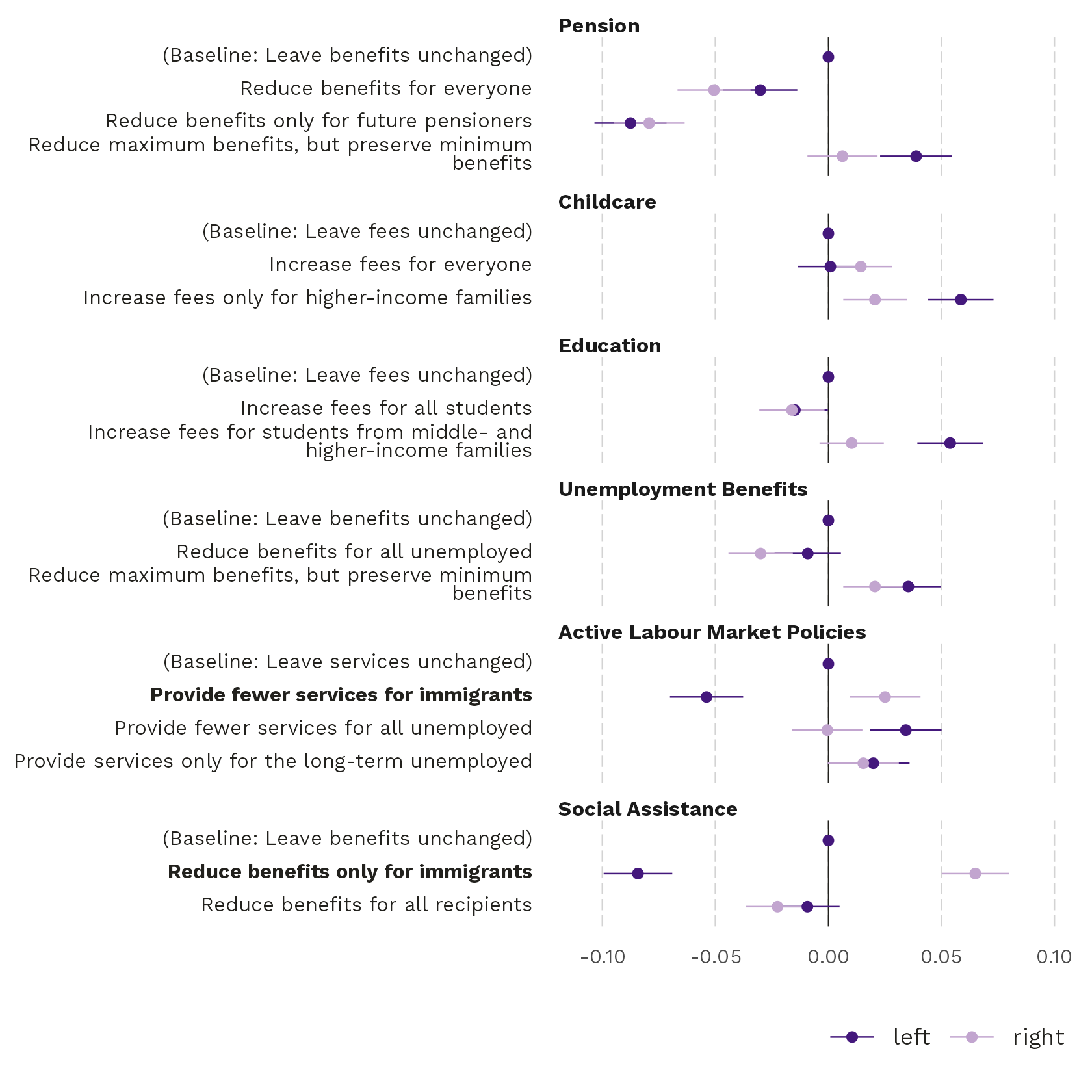

We have seen above that not a majority, but a sizeable minority of (actual or potential) left voters are willing to discriminate between immigrants and country citizens, at least when it is in the form of welfare expansion. What we do not know from the above analyses is whether left voters opposed to welfare chauvinism care enough about immigrants’ rights to make them reconsider their party choice if their party adopts welfare chauvinist positions. To assess this, we use evidence from a conjoint experiment conducted in the same survey (2018/2019, eight Western European countries) on which Figure 1 is based (see Enggist 2022). In this conjoint experiment, respondents were repeatedly confronted with two welfare reform packages. These reform packages vary randomly: in each package, some policy fields are left as they are, while in others benefits or services are cut back for everyone, are cut back only for higher income recipients, or cut back for specific groups such as immigrants. Respondents had to compare the two reform packages and indicate which of the two packages they preferred (the number of policies where everything stays the same was constant within each comparison). This analysis allows us to see whether and to what extent a reform proposal (such as providing fewer labor market activation services for immigrants or reducing immigrants’ social assistance benefits) contributes to a welfare reform being liked or disliked. A positive value in Figure 3 for a particular reform proposal indicates that reforms containing this reform proposal are relatively well liked and are chosen more often. A negative value indicates that reforms containing that proposal are less popular and are chosen less often. If a value is close to 0, it means that on average a reform proposal is neither more nor less popular than the status quo, which could indicate that people do not care very much about a reform proposal, but look at other reform proposals when deciding which reform package they prefer. Figure 3 shows the conjoint results separately for people with a left ideology (who identify themselves on a scale of 0 to 10 with a value of 0 to 4) and for people with a right ideology (values of 6 to 10).

When respondents are asked to evaluate different reform packages that cut back the welfare state (Figure 3), both right and left citizens react strongly to whether reform packages include cuts for immigrants, but they do so differently. Right-wing citizens do not like any of the retrenchment reform proposal as much as they like cutting immigrants’ social assistance benefits. Left-wing citizens, on average, dislike almost no reform proposal as much as reducing benefits and services for immigrants and thereby introducing discrimination between country nationals and immigrants. This is remarkable given that many left respondents could personally benefit from some of the other social policies proposed to be cut. Nevertheless, they seem to react to no welfare cut as strongly as to cuts for immigrants.

Similarly, when asked about reform packages designed to expand the welfare state, unequal treatment of country nationals and immigrants is a concern for both left and right-wing respondents. Right-wingers like nothing better than to expand active labor market policies or social assistance benefits exclusively for natives, while these proposals evoke a strong negative reaction among people identifying as left-wing.

Figure 3: Contribution of policy reform elements to a retrenching welfare reform package being liked more or less; individuals with a left (0-4) vs. right (6-10) ideology

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto — Data source: survey conducted

These findings are largely robust across the eight countries in which we conducted this survey. In every country except Ireland, reducing immigrants’ social assistance benefits is popular with right-wing individuals. Importantly, introducing discrimination between immigrants and country nationals is unpopular with left individuals in all countries except Denmark, where none of the welfare chauvinist reform proposals evokes significant opposition from the Left. This may indicate that the electoral risk of antagonizing existing left voters may be lower in Denmark than in other countries.

Conclusion and Implications

This research brief shows that curtailing the welfare rights of immigrants does not win a majority among the electorate of any of the most relevant left parties in the eight Western European countries studied here. Moreover, welfare chauvinism is not considerably more appealing to potential voters than to actual voters of left parties. Therefore, the pool of voters who could be easily and quickly won over by the Left with welfare chauvinist positions is relatively small (of course, we cannot rule out that in the long run people who cannot imagine voting for the Left would reconsider if left parties changed their positions).

While the potential for electoral gains from welfare chauvinist stances among likely left voters is limited, adopting welfare chauvinist stances risks losing current voters. A substantial proportion of people who identify as left-leaning care deeply about equal welfare rights for immigrants and country nationals. When a welfare reform package includes welfare chauvinism, left voters on average show strong opposition to that reform package. This suggests that for many of these left voters, a welfare chauvinist shift by their party could lead them to turn away from their party and look for another party-political home.

Although some of the (white) working-class voters that the left has the aspiration to represent do indeed support welfare chauvinism, granting more welfare rights to country nationals than to immigrants does not seem to be an electoral winning strategy for left parties in Western Europe. In particular, restricting immigrants’ rights without additional benefits for country nationals is supported only by a minority of left voters, does not seem to have the potential to attract a sizeable number of new voters, and runs the risk of alienating those (middle class) voters who care about immigrants’ rights and who now make up a sizeable proportion of almost all left parties in Western Europe.

Based on:

Enggist, Matthias (2022). “Welfare Chauvinism – Who Cares? Individual-Level Evidence on the Importance and Politicization of Immigrants’ Welfare Entitlement”. Kapitel der Dissertation.

Enggist, Matthias and Silja Häusermann (2024). “Partisan preference divides regarding welfare chauvinism and welfare populism – Appealing only to radical right voters or beyond?”. Journal of European Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1177/09589287241229304.

Harris, Eloisa and Matthias Enggist (2024). “The micro-foundations of social democratic welfare chauvinism and inclusion: class demand and policy reforms in Western Europe, 1980-2018”. European Political Science Review 34(2): 142-158. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000346.

References:

Abou-Chadi, Tarik, Silja Häusermann, Reto Mitteregger, Nadja Mosimann and Markus Wagner (2023). “Old Left, New Left, Centrist or Left National? Determinants of support for different social democratic programmatic strategies”.

Andersen, Jørgen Goul and Tor Bjørklund (1990). “Structural Changes and New Cleavages: the Progress Parties in Denmark and Norway”. Acta Sociologica 33(3): 195-217.

Careja, Romana and Eloisa Harris (2022). “Thirty years of welfare chauvinism research: Findings and challenges”. Journal of European Social Policy 32(2): 212-242.

Gabriel, Sigmar (2019). “Die SPD sollte sich am Erfolg der dänischen Genossen orientieren. Gastkommentar”. Handelsblatt, 07.06.2019. https://www.handelsblatt.com/meinung/gastbeitraege/gastkommentar-die-spd-sollte-sich-am-erfolg-der-daenischen-genossen-orientieren/24428330.html?ticket=ST-845243-qFdcZsPYsSh3PUi1FO9e-ap5.

Gingrich, Jane and Silja Häusermann (2015). “The decline of the working-class vote, the reconfiguration of the welfare support coalition and consequences for the welfare state”. Journal of European Social Policy 25(1): 50-75.

Häusermann, Silja (2023): “Social Democracy in competition: voting propensities, electoral potentials and overlaps.

Häusermann, Silja and Hanspeter Kriesi (2015): “What do voters want? Dimensions and configurations in individual-level preferences and party choice”. In: Pablo Beramendi, Silja Häusermann, Herbert Kitschelt and Hanspeter Kriesi (eds.): The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. Cambridge University Press, 202-230.

Oesch, Daniel and Line Rennwald (2018): “Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: Class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right”. European Journal of Political Research 57(4): 783-807.

Trimborn, Marion (2023): “Sarah Wagenknecht: ‘Mir Rassismus vorzuwerfen ist aberwitzig’. Interview mit Linken-Politikerin”. Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung, 09.09.2023. https://www.noz.de/deutschland-welt/politik/artikel/migration-begrenzen-sahra-wagenknecht-im-interview-45460426.

Note: This article was published as a research brief by PPRNet.

Image: flickr.com