The myth we address in this research brief states that there is a deep rift that cuts through the progressive political field in the early 21st century. In this research brief, we make use of recent empirical survey research to show why this diagnosis is wrong. Instead, the analyses show that economically decidedly left voters clearly support culturally progressive programs and vice versa.

A rift between material and post-material policy stances?

The electoral crisis of social democratic parties has led to an ongoing debate about their programmatic profile. This debate is often framed around the distinction of a material – i.e. socio-economic – and a post-material – i.e. socio-cultural – orientation of these parties.

Material issues concern questions of distribution, redistribution and state involvement in the market. They include issues such as measures of social security, the economy or taxation and are often regarded as the historical core of what traditional social democracy – or the Left in general – stand for. Left positions signal support for strong state interventionism, high fiscal taxation and strong levels of redistribution from the upper income strata to the lower ones. Post-material issues on the other hand focus on questions of social justice such as gender equality, racism, integration and inclusion, or LGBTQ+ rights. Left positions in the realm of post-material politics signal support for an extension of political rights and social support for women, migrants, and other minoritized groups.

In its most simple form, this distinction is referred to as either an “economic” or a “cultural” issue, and it is often argued that progressive politics has originated in economically progressive stances and has increasingly evolved towards more culturally progressive programs.

It has become a common theme in the debate about the programmatic direction of social democratic parties to think of a divide in the left field based on these material and post-material issues. This idea assumes that the working class and lower educated voters – the former core electorate of the Left – is in favor of material redistribution but opposes culturally progressive measures on gender equality or immigration. In contrast, educated middle class voters – the other core group that parties of the Left need to appeal to – prefer progressive cultural policies but do not want redistribution. Based on this distinction many commentators diagnose a dilemma of the Left (see also the PPRNet Research Brief “Why welfare chauvinism is not a winning strategy for the Left” by Matthias Enggist). In addition, as the electorate of the Left now includes many more educated professionals than it used to, many diagnose a shift from the Left’s material core issue to a post-material Left largely focused on social justice issues. Even more sophisticated academic analyses come to the conclusion that a focus on the demands of an educated middle class, has led especially social democratic parties to move away from the Left’s core business of redistributing income and wealth (Piketty 2020, for a discussion of this topic, see the PPRNet Research Brief “Why the rise of the greens does not threaten the welfare state” by Hanna Schwander and Björn Bremer).

Three wrong assumptions

Here, we argue that the narrative of a Left divided between material and post-material demands is based on three assumptions that do not hold up to empirical scrutiny. First, these arguments often imply a form of socio-structural determinism, assuming that parties need to and can mobilize entire social classes. Second, and building on the former, it is assumed that educated middle class voters are opposed to strong state interventionism and redistribution. Third, it is likewise assumed that the working class opposes culturally progressive positions. These assumptions are at odds with empirical research on these questions and thus mislead us to wrong conclusions about a divided Left.

First, we can be misled by the idea that political parties need to address allegedly homogeneous interests of entire social classes. Indeed, for analytical theoretical purposes, research on electoral behavior often divides society into different socio-economic groups (e.g. the working class or the middle class) with different group preferences that make certain party attachments more likely and more prevalent. In academic work as much as in the public debate, we thus often read that certain groups want more or less redistribution or that a party needs to appeal to a specific group to be successful. There is indeed ample empirical evidence that socio-economic class groups have diverging preferences on important political issues and that they, in turn, shape patterns of political competition (Oesch and Rennwald 2018). This perspective, however, involves the risk of curtailing the argument to socio-structural determinism. While it is true that a member of the working class is on average less progressive on immigration than a socio-cultural professional, by no means are all working class members less progressive than socio-cultural professionals. Left parties cannot and do not need to respond to the attitudes of all members of the working class or of the educated middle classes. Hence, knowing the average attitude of a working class member does not have direct implications for the electoral opportunity or risk of taking a specific position. Hence, while group-based preferences are an important way of thinking about trade-offs of programmatic appeals, there is a risk in oversimplifying these relationships and jumping to sweeping conclusions. Such a perspective then necessarily exacerbates the assumed divides within the electorate.

The other two assumptions concern the preferences of middle- and working class voters. According to the narrative of a divided Left, educated middle class voters that are better off economically, are expected to oppose or devalue attempts by the Left to redistribute income and wealth. As this growing group of voters takes up an increasing share within the social democratic electorate, there is a fear that social democrats cannot appeal to middle class voters unless they move away from redistribution. A mirror-image important element in the narrative of a divided left is the idea that working class and lower educated voters reject culturally progressive positions on immigration, gender equality of LGBTQ+ rights. It follows that parties of the Left can either appeal to economically left voters or socio-culturally progressive ones.

There is a large amount of research that puts this oversimplified idea of class preferences and their role for supporting the Left into doubt. First, the narrative is based on a wrong idea of middle-class preferences in post-industrial societies. There is already an abundance of research that documents that new middle class groups are strongly in favour of redistributive measures and the welfare state, although they might not directly benefit from it (Abou-Chadi and Hix 2021; Häusermann and Kriesi 2015, Kitschelt and Rehm 2014). Hence, while educated middle class voters indeed care about progressive post-material positions, they by no means object to economic redistribution. And while it is true that especially education is correlated with more progressive attitudes (while income per se is not), there is a very large share of working class voters that are in favour of progressive measures on issues such as immigration, LGBT rights or climate change (Abou-Chadi, Mitteregger, and Mudde 2021). Therefore, less progressive socio-cultural positions of social democratic parties do not lead to more working class support (Abou-Chadi and Wagner 2020).

Here, we also want to emphasize an additional point that is often neglected in the debate around a divided left. Simply put, not all voters are available to programmatic appeals by parties of the Left. While we might find differences in attitudes in the electorate as a whole, the crucial question is how trade-offs play out in the potential electorate of the Left. Parties of the Left do not need to appeal to all working class or middle class voters, but only to those that they can reasonably expect to reach with their programmatic choices. If we accept that some voters are extremely unlikely to ever vote for a party of the Left, what do the resulting trade-offs looklike for those that they can reasonably appeal to? Here, we present evidence on what kind of social democratic program voters in their potential electorate want.

Testing support for different programs

In recent research, we were able to assess the potential preference divides in the wider left electorate head-on. We asked survey respondents in six Western European countries (Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and Spain) to choose between stylized social democratic programs (Abou-Chadi et al. 2024).

In order to represent the different strategic choices that progressive parties make, we distinguished between four types of programs. First, let us imagine progressive parties that actually perceive that there is a choice to be made between an economically progressive program that turns its back on cultural liberalism – supposedly in order to appeal to economically motivated working class voters. This party would most likely choose a “left-national” program, implying decidedly left-wing economic stances and more moderate-to-conservative positions on post-material, socio-cultural issues. The other strategic choice is a “new left” program, emphasizing socio-culturally progressive stances, while being somewhat more moderate or centrist on economic issues. What we call an “old left” combines radical positions on economic distribution with moderately progressive positions on cultural issues. And finally, progressive parties that try to evade the question by adopting centrist, moderate positions on both economic and cultural topics.

In our survey, we let responds choose between stylized programs that include policy positions on issues such as pensions, child care, immigration, or CO2 taxation. We chose these issues to represent the ideal types above (for details, see Abou-Chadi et al. 2024). Based on this data we can then answer two central questions for the potential social democratic electorate: which of these programs is generally more popular? and can we see divides within this electorate in terms of popularity of programmatic bundles?

How did people in the potential social democratic electorate – defined as all respondents who indicate a probability to vote social democratic of 50% or higher and/or who position themselves on in the centre or on the left of the political spectrum (in total about 55% of respondents in our sample) – rate the different programmatic combinations? We can see that centrist and left-national programs receive much less support than old left and new left programs. There is no statistically significant difference between support for old and new left programs. Hence, for the overall social democratic electorate new left and old left programmatic bundles are more popular than their alternatives.

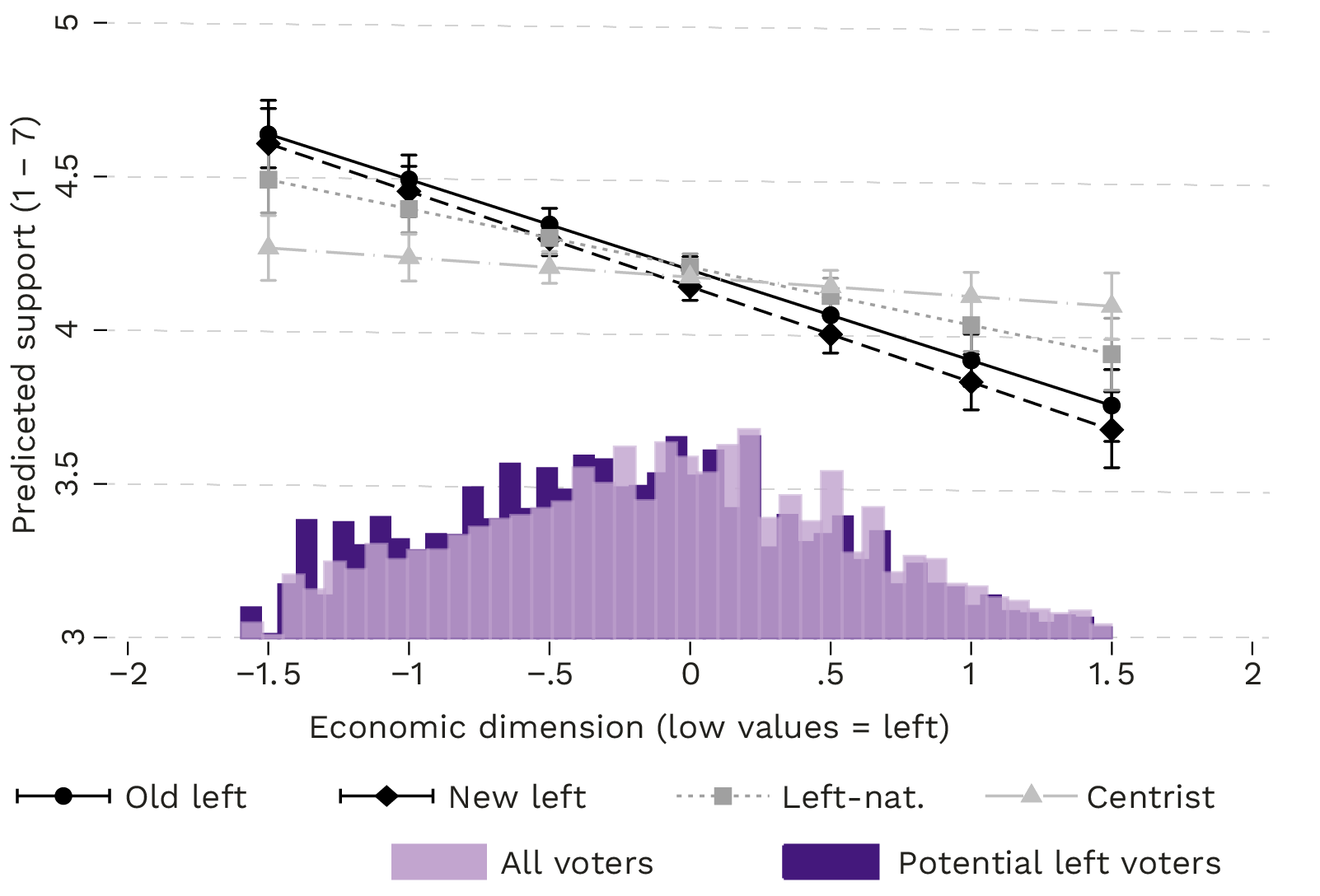

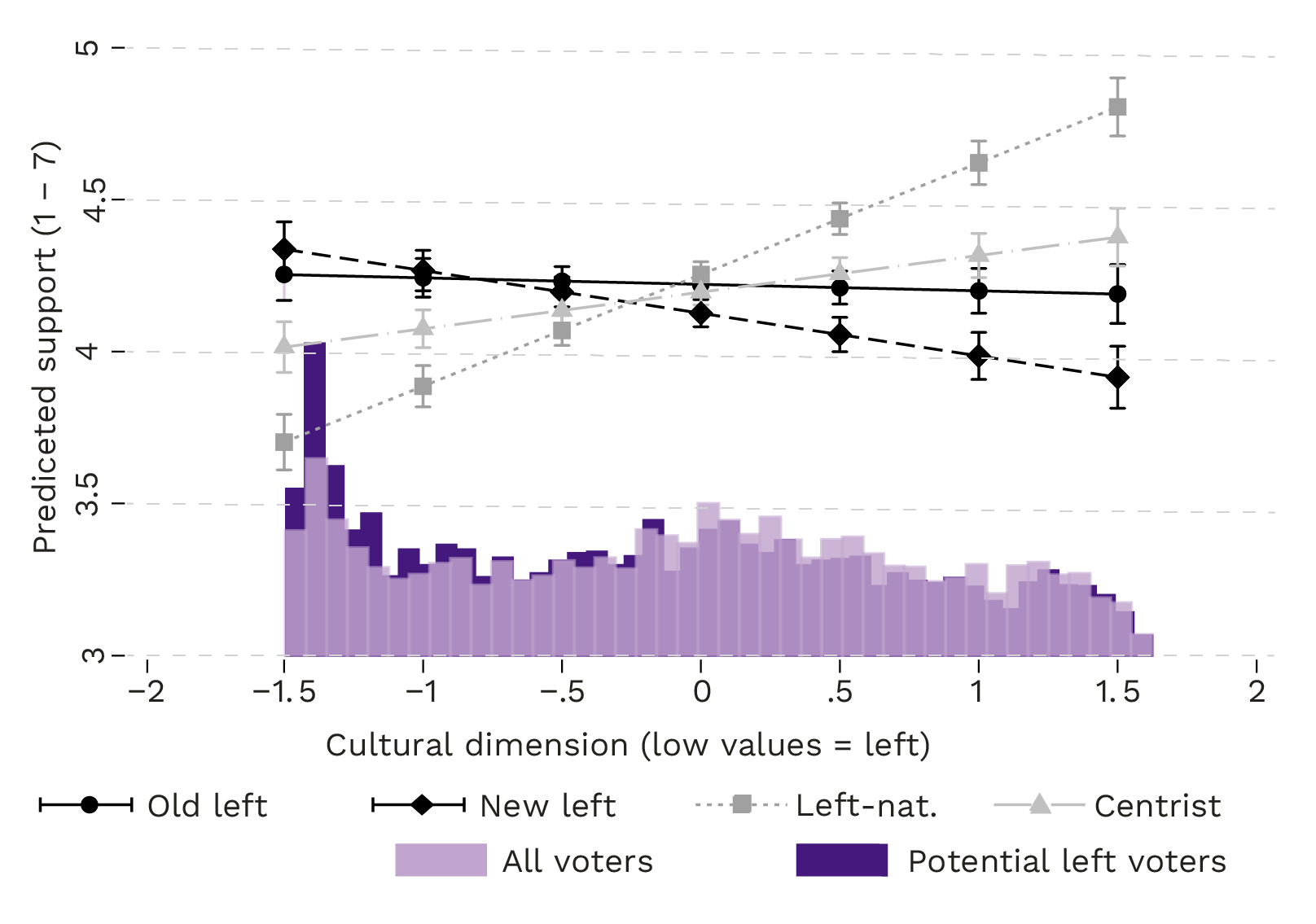

Our main question, however, was about a potential divide among voters that social democrats can potentially reach. In Figures 1 and 2, we thus show how people evaluate different programmatic bundles based on their own political attitudes. How do economically left and culturally progressive people evaluate the programs? Is there a divide?

Figure 1 shows the support for the four programmatic types on the y-axis based on people’s economic attitudes on the x-axis (measured through a battery of questions about redistribution, the welfare state and state intervention). The figure additionally shows how potential social democratic voters highlighted in black bars (versus the electorate as a whole highlighted in grey bars) are distributed on this dimension of economic attitudes from left to right. As we would expect, we see that the electoral potential of Social Democratic parties (the black bars) are concentrated on the left side, i.e. these voters on average have economically left-wing positions. We now want to know if those who are strongly to the left on economic issues have a significantly weaker support for culturally liberal, new left programs. This is clearly not the case: we find that for those that are economically left, new left and old left programs are both slightly more popular than left-national programs. Centrist programs are the least popular in this group. Hence, it is not at all the case that left-national programs receive more support among the economically left-wing.

Figure 1 – Support for program types conditional on economic attitudes

2

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto – Data source: Abou-Chadi et al. 2024

Figure 2 – Support for program types conditional on socio-cultural attitudes

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto – Data source: Abou-Chadi et al. 2024

Figure 2 repeats this analysis to see if strongly progressive voters on cultural, post-material issues indeed have lower support for traditional, old left programs. Again, we find no evidence for this pattern, which would be a precondition for the dilemma to materialize. Figure 2 shows the support for the four different program types based on socio-cultural attitudes (based on a battery of items including attitudes toward LGBT rights, immigration and gender equality). We can see that among the culturally progressive – a group that is strongly overrepresented in the potential social democratic electorate – new left and old left are both significantly more popular than centrist and left-national programs. Between new left and old left programs there are no significant differences. In sum, new left and old left programmatic strategies find the highest level of support among both economically left and culturally progressive voters.

Conclusion

The idea of a Left divided between materialist left and post-material progressive voters has been a powerful narrative shaping a lot of commentary and strategic considerations. In this brief, we document that in light of empirical data, it turns out to be largely a myth. In general, we find that generally economically left-wing and culturally more progressive positions are most popular within the very broad potential electorate of social democratic parties. Those that have economically left-wing attitudes also want socio-culturally more progressive policies. Those that are more culturally progressive prefer programs that are economically left. Hence, there is little empirical evidence in support of a material/post-material dilemma on the Left. Progressive parties have the potential to form an electoral coalition based on economically left as well as culturally progressive positions. The myth of a divided Left has stood in the way of formulating such an agenda for future decades.

Based on:

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, Silja Häusermann, Reto Mitteregger, Nadja Mosimann, and Markus Wagner. 2024. “Old Left, New Left, Centrist or Left Nationalist? Determinants of support for different social democratic programmatic strategies.” in Silja Häusermann and Herbert Kitschelt (eds). Beyond Social Democracy. The Transformation of the Left in Emerging Knowledge Societies. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Access here: https://osf.io/fehzr

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik. 2023. “The myth of a divided Left”. Renewal 31 (4): 21-24.

References:

Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Simon Hix. 2021. “Brahmin Left versus Merchant Right? Education, class, multiparty competition, and redistribution in Western Europe.” The British journal of sociology 72 (1): 79–92.

Abou-Chadi, Tarik, Reto Mitteregger, and Cas Mudde. 2021. “Left behind by the working class?: Social Democracy’s Electoral Crisis and the Rise of the Radical Right.” Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Empirical Social Research.

Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Markus Wagner. 2020. “Electoral fortunes of social democratic parties: do second dimension positions matter?” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (2): 246–72.

Häusermann, Silja, and Hans-Peter Kriesi. 2015. “What Do Voters Want? Dimensions and Configurations in Individual-Level Preferences and Party Choice.” In The politics of advanced capitalism, eds. Pablo Beramendi, Silja Häusermann, Herbert Kitschelt and Hans-Peter Kriesi. New York: Cambridge University Press, 202–30.

Oesch, Daniel, and Line Rennwald. 2018. “Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: Class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (4): 783–807.

Piketty, Thomas. 2020. Capital and ideology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Note: This article was published as a research brief by PPRNet.

Image: flickr.com