A key myth about social democracy is that its decline is directly related to the rise of the radical right across Europe as a result of policy choices on issues such as immigration. Using several data sources and research tools we show that social democrats in Western Europe have lost only a small share of their voters to the radical right. At the same time, only few of today’s radical right supporters previously identified with social democracy and only few people consider voting for both a social democratic and a radical right party.

The myth

Social democratic parties in Western Europe have witnessed strong electoral decline in the past two decades. At the same time, radical right parties have seen significant gains in elections. At first glance, it seems obvious to link these two trends as the rise of the radical right has taken place at the same time as the decline of the social democrats. There is also a superficial plausibility to this link. In many countries, radical right parties receive strong support from working-class voters.

This pattern, observed in many settings, has created a two-part myth that many scholars, journalists and other observers of politics have promoted and seemingly internalized. First, working-class social democratic voters have defected from their natural home and shifted their support to radical right parties. Second, social democratic parties could win back these voters by appealing to them more directly, for instance by taking tougher stances on immigration. This would – so the narrative goes – win voters back from the radical right and so at the same time strengthen social democracy and weaken the radical right.

Evidence 1 – No direct vote switching from social democrats to the radical right

There are two crucial questions that we address in this section: (1) What parties have social democratic parties lost their voters to? (2) What kind of voters have social democratic parties disproportionally lost, and to whom?

In order to study these questions we have compiled survey data that allows us to analyze patterns of vote switching. We compile data on current and previous vote choice in Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.

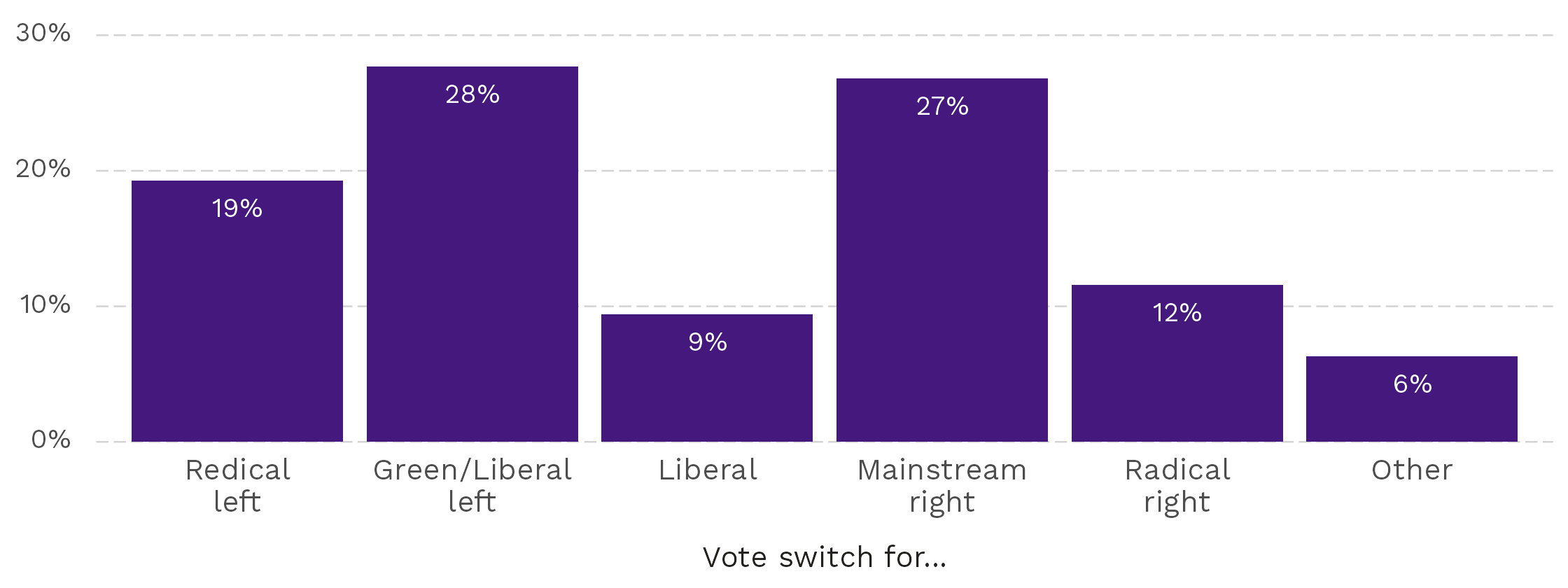

Figure 1. Vote switching from SD parties to other party families

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto

In Figure 1 we show which party families former social democratic voters left for. Three noteworthy patterns stand out. First, social democrats have lost by far the largest share of voters to parties that are generally economically and/or culturally to their left: Green/left-libertarian and radical left parties. Second, an important share has gone to competitors on the mainstream right. Third, only a small share of voters has switched from a social democratic to a radical right party. Our first findings, thus, clearly speak against the myth of vote losses to the radical right. Losses to the center and to the progressive-left are thus at the heart of social democratic vote losses – losses to the radical right are not. These are clearly divided among voters of different education level with voters of medium and high levels of education switching to Green/left-libertarian parties while the less-educated opting most for the mainstream right.

Evidence 2 – Long-term patterns of vote switching

To understand the long-term patterns we turn to panel data tracking the same respondents in Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom across a time span of 30 years. To conduct our analyses we need a consistent identification of social democratic “core” voters across time and space. We decided to use a conservative strategy and define a social democratic voter as someone who repeatedly votes for the social democrats.

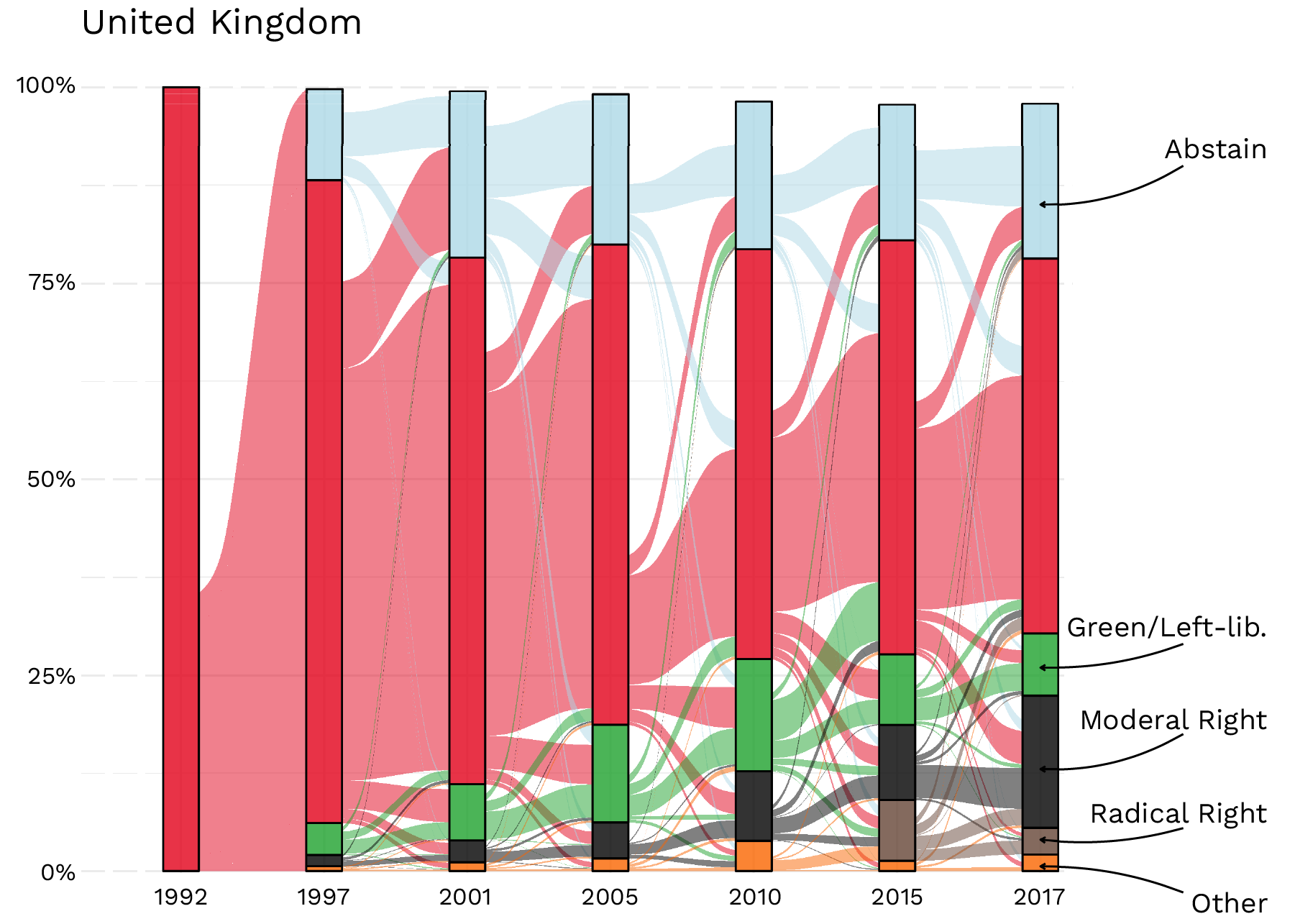

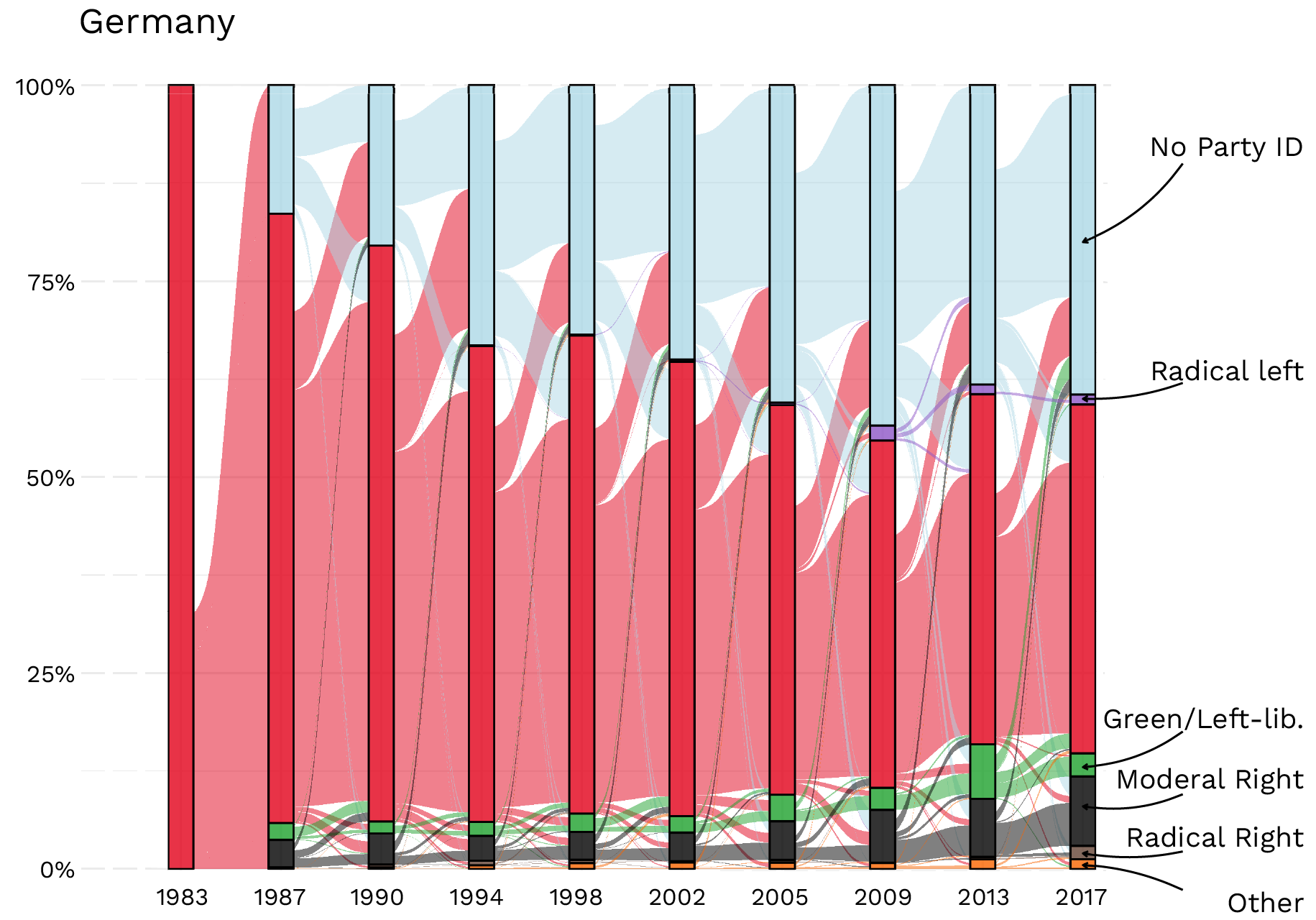

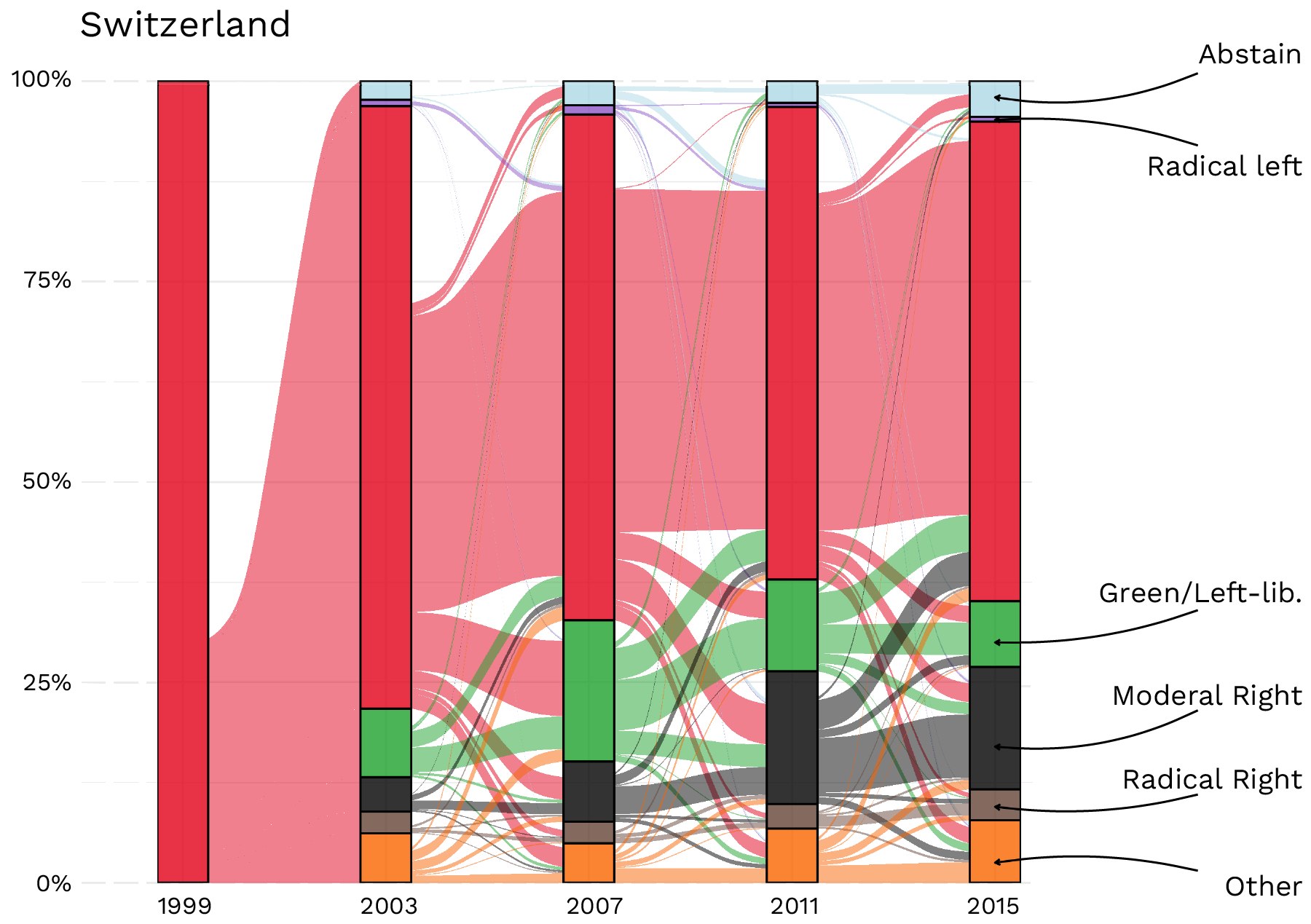

In contrast to the public narrative we find little support for the notion that social democrats are defecting to one particular party. Our findings indicate that social democrats lose their voters in all directions, but that most former social democrats appear to be the de-mobilized voters of today.

If anything, social democrats in all three countries moved to progressive options – the Greens in Germany, the Liberal Democrats in the UK and the Green and, especially, the Green Liberal Party in Switzerland. Even more worrisome is the following: in all three countries social democrats struggle to attract “new voters”. This pattern is strongest for the German SPD: the SPD loses its core without finding means to attract “new voters”.

Figure 2. Transition away from social democrats in the UK, Germany, and Switzerland

Figure : Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto

Evidence 3 – Probability to vote for other parties

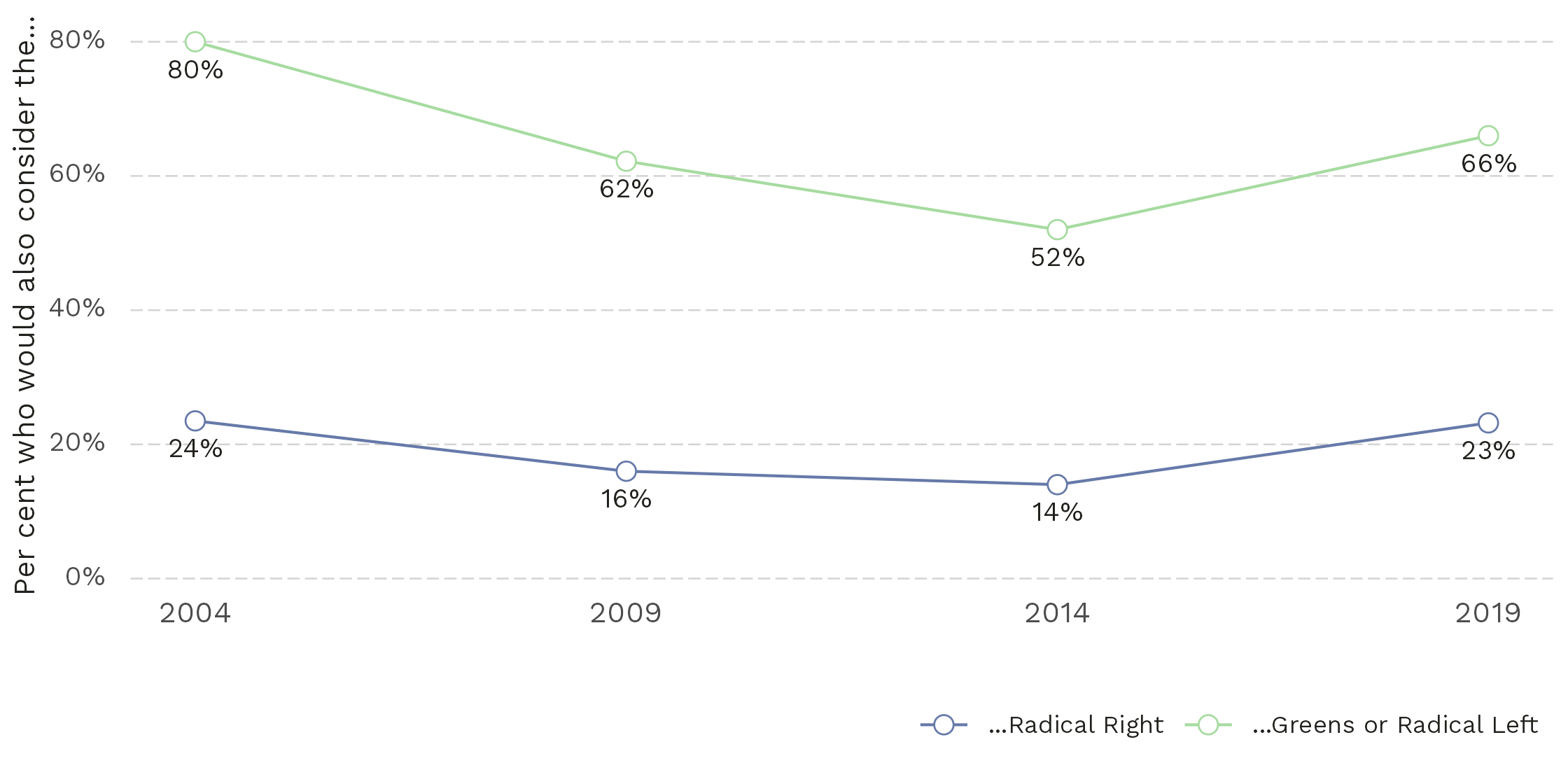

We provide a third set of evidence that speaks against the myth that the electoral crisis of social democratic parties is driven by vote losses to the radical right. We are interested in finding out how many people who would consider voting for a social democratic would also consider voting for a radical right party, using survey data from Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK. People are asked on a 0 to 10 scale how likely it is that they would ever vote for a party in their country. We code someone as a potential voter of a party when they score a party higher than 5 on this scale.

Figure 3. Share of people who would consider voting for the Social Democrats who would also consider voting for the radical right, or the greens or radical left

Figure : Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto

Figure 3 shows the share of people that would consider voting for a social democratic party that would also consider voting for a radical right or a Green/left-libertarian party. We can see that over the last 20 years less than 20% of the people who would consider voting for a social democratic party would also consider voting for the radical right. This is dwarfed by the over 60% that would consider voting for a Green/left-libertarian party. This is in line with research indicating that social democratic and green/left-libertarian voters share similar policy positions on many issues including social policy and the welfare state. This underlines two things. First, there is only a small share of radical right supporters that social democratic parties can reach even potentially. Second, strategies to appeal to these voters will come with the very high risk of losing many more to more progressive parties.

Conclusions and implications

In this research brief we have provided empirical evidence from multiple sources that very clearly contradicts the myth that the electoral decline of social democratic parties is driven by vote losses to the radical right. Our findings also speak against the idea that strategies to win back working-class voters from the radical right by taking more anti-immigrant or other less progressive positions will work for social democratic parties. One important and often overlooked pattern that we document here is that social democratic parties have struggled to attract new voters. Hence, instead of focusing on how they have lost, social democratic parties might be better advised to devise strategies to win new voters.

References

Abou-Chadi, Tarik, Denis Cohen and Markus Wagner. 2022. “The centre-right versus the radical right: the role of migration issues and economic grievances.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48(2):366–384.

Krause, Werner, Denis Cohen and Tarik Abou-Chadi. 2023. “Does accommodation work? Mainstream party strategies and the success of radical right parties.” Political Science Research and Methods 11(1): 172–179.

Based on

Abou-Chadi, Tarik and Markus Wagner. 2023. “Losing the Middle Ground: The electoral decline of Social Democratic parties since 2000.” In Häusermann/Kitschelt Beyond Social Democracy: The Transformation of the Left in Emerging Knowledge Societies. Access here: https://osf.io/m7azv/

Bischof, Daniel and Thomas Kurer. 2023. “Lost in Transition – Where Are All the Social Democrats Today?” In Häusermann/Kitschelt Beyond Social Democracy: The Transformation of the Left in Emerging Knowledge Societies. Access here: https://osf.io/n2hbu/

Picture : Unsplash.com

Note : This article has been edited by Robin Stähli, DeFacto.