Progressive parties face challenges to rally the declining manufacturing working class and the socio-cultural professionals because of their different stances on the political spectrum. Although it is often argued that appealing to the service workers – the “new” working class – can overcome this challenge, this contribution reveals that cultural issues also tend to divide the socio-cultural professionals which are more closely aligned with the new left and service and manufacturing workers remaining closer to social-democratic parties.

Situating the myth: social class and voting in the knowledge economy

Policy preferences and electoral behavior are heavily influenced by social class, understood as the position that one occupies in the employment structure. Two key transformations distinguish the class conflict in post-industrial societies from industrial economies: first, the stark decline of the working class explained by the lower number of manufacturing occupations as well as the growth of the service sector and the general expansion of higher education; second, the reliance of left-wing parties over the middle-class electorate to mitigate the decline of their core electorate.

However, the recent attempts to their joint mobilization do not come without challenges for the left: socio-cultural professionals display more liberal positions on cultural issues, while production workers take more authoritarian and nationalist positions (Oesch & Rennwald, 2018). This can pose problems for the left when these topics become strongly politicized. Even if some left-wing sections of the working class might display progressive cultural attitudes, the lack of an overlap in the economic and cultural preferences of socio-cultural professionals, and service and manufacturing workers generates challenges for the left.

The myth: a natural service cross-class coalition?

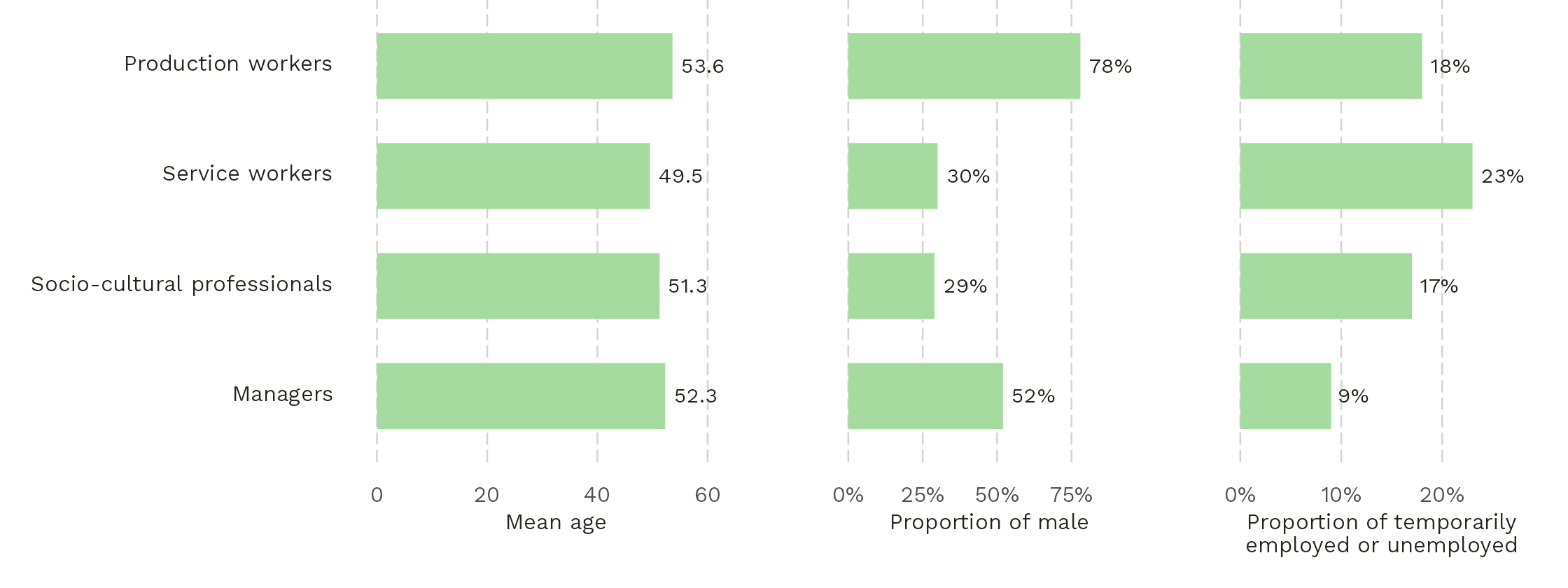

Some have argued that there are greater similarities between the “new” working class, i. e. low-skilled workers in the service sector, and the socio-cultural professionals, and that these similarities could help left-wing parties to overcome the difficulties mentioned earlier. Two things characterize both the low-skilled workers and the socio-cultural professionals, namely their demographic composition and the nature of their jobs. As shown in Figure 1, in their likeliness of being female as well as in their exposure to temporary employment or unemployment socio-cultural professionals are closer to service workers than to other middle-class occupations (like the managerial class).

Figure 1. Socio-demographic profile of selected classes

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Note: Descriptive statistics based on European Social Survey data collected between 2020 and 2022 in 15 Western European countries.

Socio-demographic similarity and political difference: policy preferences of the working and middle classes

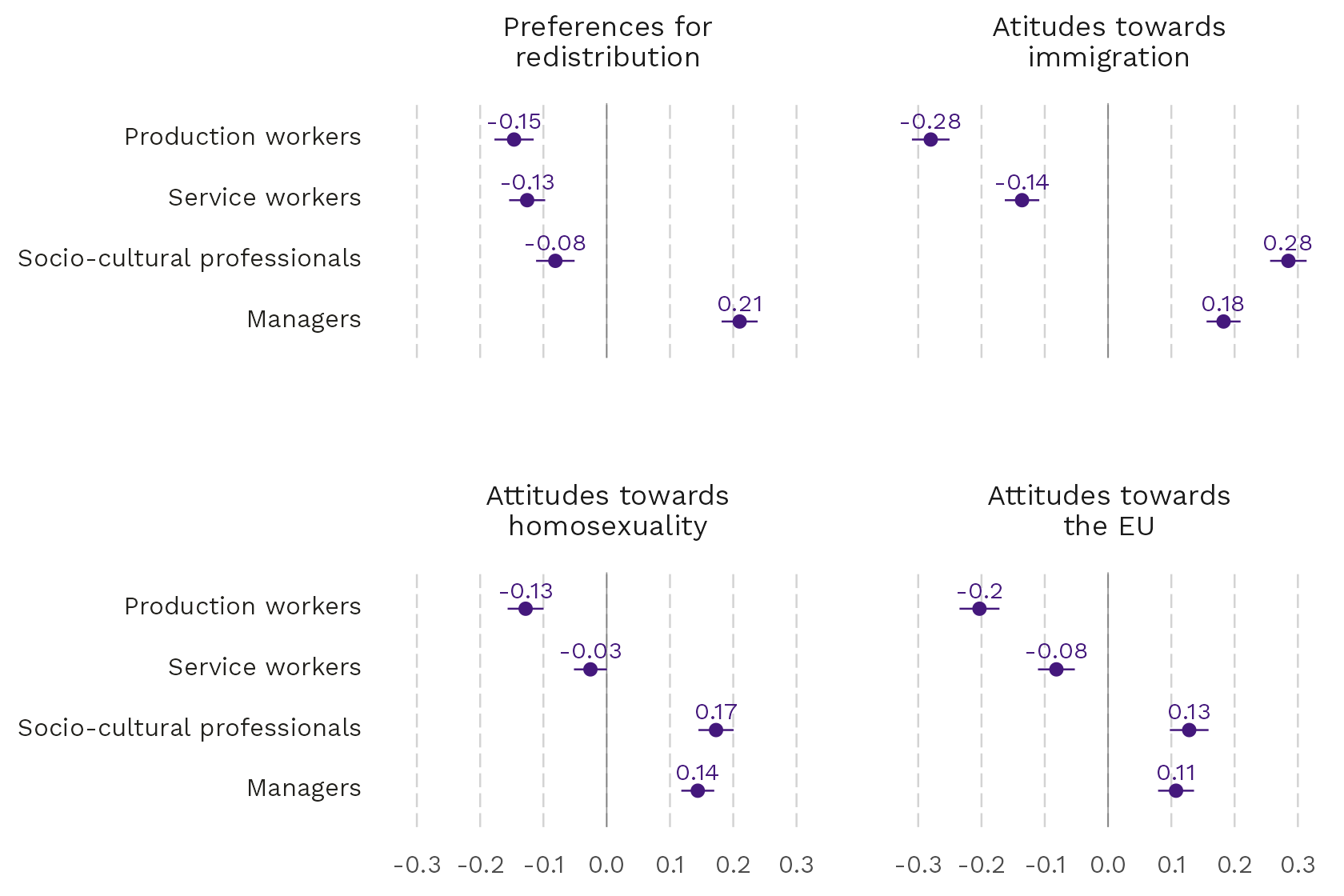

The key takeaway from the comparison of policy preferences across social classes is the following: while service workers are marginally more culturally libertarian than production workers, they are by no means close to socio-cultural professionals on these issues. These three classes display, on average, agreement on the question of income redistribution, favoring greater state intervention, in stark opposition to the market-liberal preferences of the managerial class (a traditional electorate of the right). However, on cultural issues there are differences between the average placement of the working class and socio-cultural professionals. On all three topics service workers are positioned, together with production workers, on the authoritarian pole of the spectrum (the 0 line indicates the sample mean preference on each of these issues) in clear contrast to the middle classes favoring libertarian positions. The challenges of jointly mobilizing the working class and the new middle class remain, whether the electorate targeted are production or service workers.

The differences in preferences between socio-cultural professionals and service workers become more marked in contexts in which these issues are strongly politicized by parties. That is, where political parties take distinct positions on cultural issues and these topics are salient in their agendas, differences in preferences between social classes are magnified.

Figure 2. Average predicted preferences by social class across four issues

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Data source: European Social Survey (ESS) Round 10 (2020-2022), restricted to 15 Western European countries. Outcome variables are standardized, x-axis captures distance in standard deviations from the mean, which is represented by the value 0. · Note: Estimations based on OLS regression controlling for gender, age, trade union membership, type of contract (permanent vs. temporary), and country fixed effects.

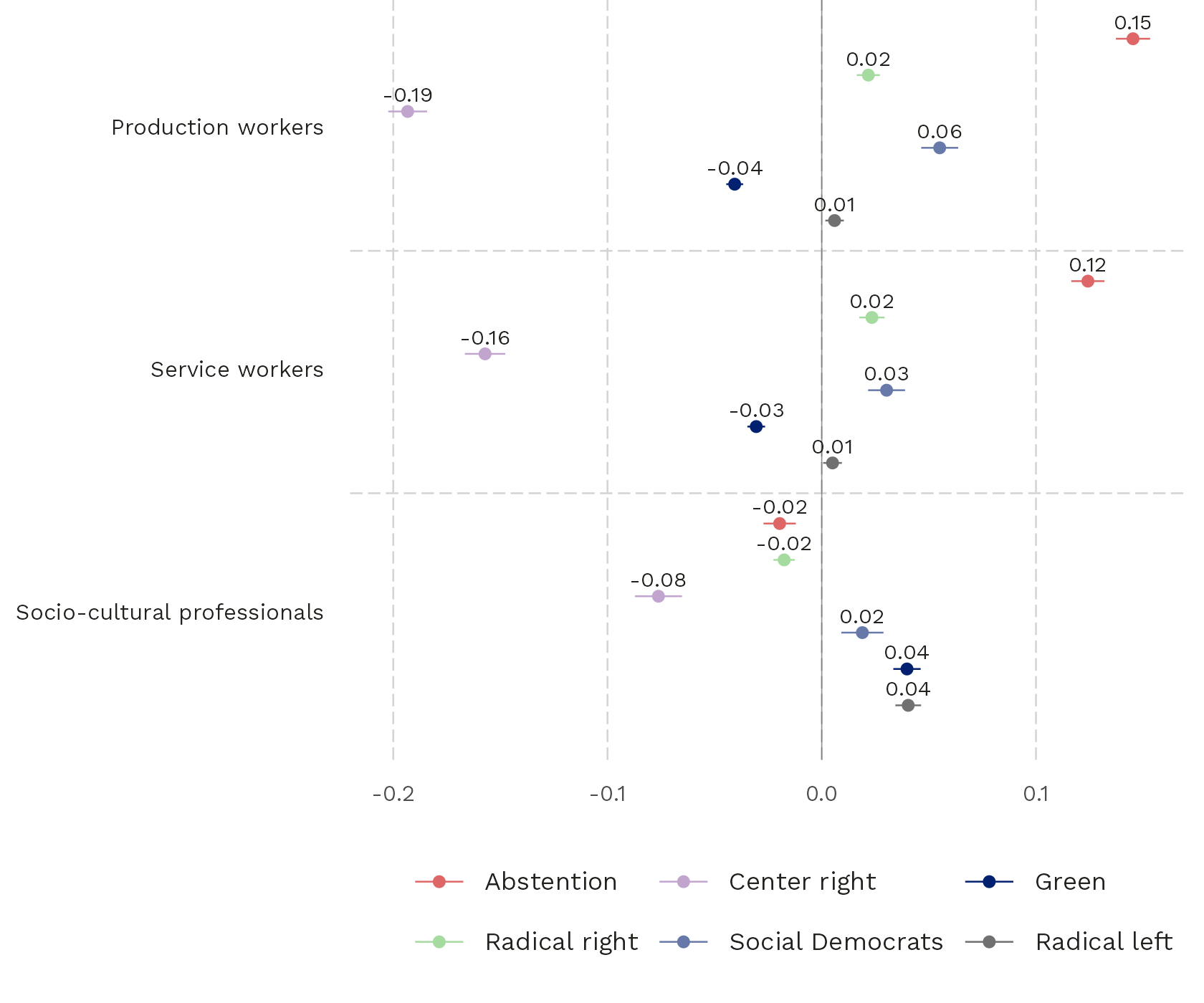

From preferences to behavior: for which parties do service workers vote?

The three classes on which we focus have a higher propensity to vote for left-wing parties, as shown in Figure 3, whether radical left (especially socio-cultural professionals) or social-democratic (especially production workers), as well as a markedly lower likelihood of voting for the mainstream right. The cultural division in preferences between the “new” middle class and workers is evident in their dissimilar support for the greens and the radical right. While socio-cultural professionals display a higher likelihood of voting green, this is not the case for workers who, instead, are more likely to vote for the radical right. Socio-cultural professionals and workers also differ markedly in their probability to abstain, the latter are more than 15 percent more likely to not have voted in the last national election.

Two findings stand out from these analyses. First, all three classes constitute relevant left-wing electorates, although with different profiles within this ideological block. Socio-cultural professionals have a higher tendency to support new left alternatives, while production workers are more closely aligned with traditional left-wing parties. Second, these three classes differ mostly in their level of political participation. Higher levels of abstention among workers indicate that there is margin to mobilize these individuals, and this could be in favor of a left-wing coalition.

Figure 3. Differences in electoral behavior by respondents’ class (with respect to the managerial class)

Figure : Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Note : Average marginal effects of respondents’ social class on support for different party families. Each coefficient indicates differences in support for each specific class in comparison to the managerial class. Analyses based on ESS data for 2002-2010. Figure adapted from Figure 4.2. in Ares & van Ditmars (forthcoming).

Conclusion: a loose coalition between workers and socio-cultural professionals?

The findings here reviewed provide insights about the potential for parties to directly appeal to these different groups at the same time. While a cross-class service coalition is not as obvious as some might expect, there are possibilities for parties to build bridges in this direction, especially when considering the socio-demographic similarities between service workers and professionals. These, expressed in terms of gender, age and atypical employment could provide a starting point to craft and mobilize a new progressive political identity. Moreover, service workers appear moderately more libertarian than production workers on some of the issues analyzed.

A coalition in support for the left across these three classes can be more easily articulated around a strong redistributive agenda. The working classes and socio-cultural professionals share a concern for economic redistribution and a strong welfare state. This can explain why turning to the right on economic issues reduces the appeal of left-wing parties among some of their core electorates.

Finally, it is important to point out that all workers display higher levels of electoral abstention, which indicates an electoral potential that is currently untapped. Their mobilization could improve the performance of the progressive block not only in the short term. It could also generate an enduring left-wing attachment for those being socialized in the service class in the contexts of their families, as studies of intergenerational political transmission have shown.

References:

Ares, M. (2017). A new working class? A cross-national and a longitudinal approach to class voting in post-industrial societies [European University Institute]. http://hdl.handle.net/1814/49184

Ares, M. (2020). Changing classes, changing preferences: How social class mobility affects economic preferences. West European Politics, 43(6), 1211–1237. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1644575

Oesch, D., & Rennwald, L. (2018). Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: Class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right. European Journal of Political Research, 57(0), 783–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12259

Based on

Ares, M. (2022). Issue politicization and social class: How the electoral supply activates class divides in political preferences. European Journal of Political Research, 61(2), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12469

Ares, M., & van Ditmars, M. M. (2022). Intergenerational Social Mobility, Political Socialization and Support for the Left under Post-industrial Realignment. British Journal of Political Science, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000230

Ares, M., & van Ditmars, M. M. (forthcoming). Who continues to vote for the left? Social class of origin, intergenerational mobility and party choice in Western Europe. In S. Häusermann & H. Kitschelt, Beyond Social Democracy: Transformation of the Left in Emerging Knowledge Societies. Access here: https://osf.io/preprints/osf/76hn8

Note: this article has been edited by Robin Stähli, DeFacto.

Picture: Unsplash.com