As generative AI rapidly enters workplaces, a crucial question emerges: how do workers respond when they actually use this technology? The answer matters enormously for social policy and political stability. Our experimental study of over 1,000 adults in the UK reveals a surprising pattern that challenges decades of research on automation: AI exposure doesn’t increase fear of job loss, yet paradoxically strengthens support for policies helping others adapt to technological change.

For decades, political economy research on new technologies has relied on the “risk-insurance framework.” According to this model, technological exposure increases people’s perceived risk of job loss, which in turn drives demand for social policies like unemployment benefits. This pattern by and large held for previous waves of automation: robotization and routine-biased technological change disproportionately affected blue-collar workers, who responded by demanding compensatory policies.

We expected generative AI might follow the same script. In our pre-registered experiment, conducted in July 2023, participants completed three realistic work tasks: improving a workplace email, evaluating conflicting arguments, and answering questions about complex texts. We randomly assigned them to two groups which were instructed to complete the tasks either with or without the help of ChatGPT. We then measured their perceptions of job risk and policy preferences.

More Support for Social Policy, Despite Lower Risk Perceptions

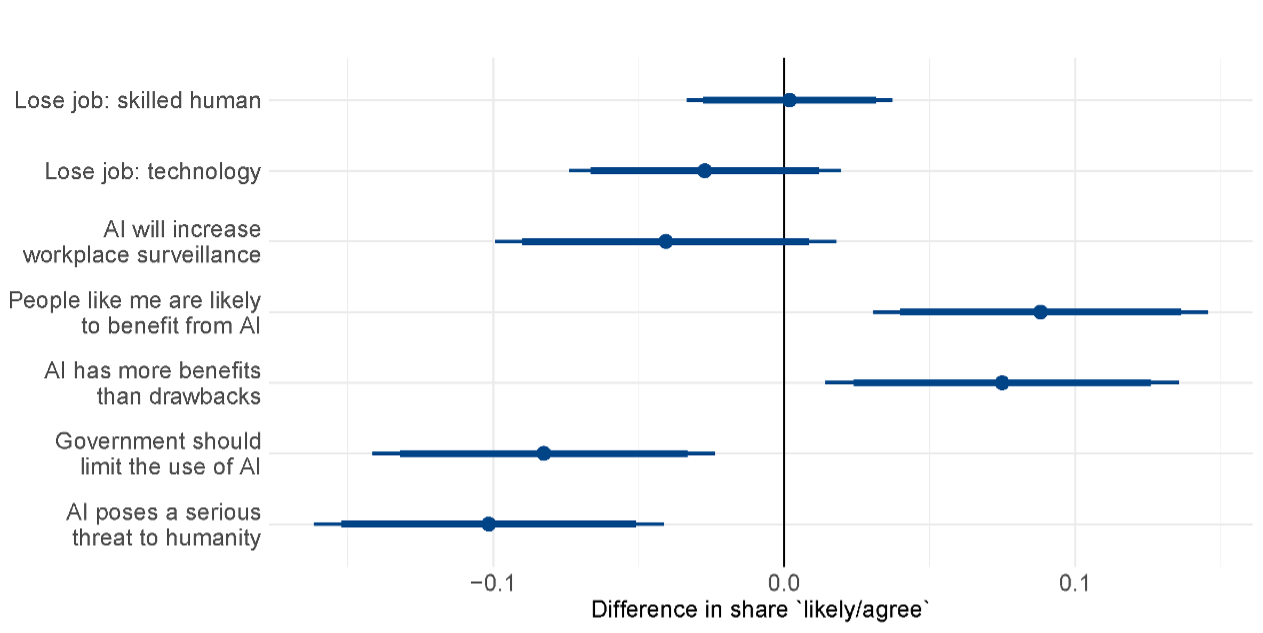

The findings were surprising: respondents who used ChatGPT were no more likely to fear job loss than those who completed the tasks without AI assistance, as Figure 1 shows. Despite experiencing firsthand how AI enhances productivity on common workplace tasks, they didn’t perceive greater threats to their employment prospects. In fact, they developed significantly more positive attitudes toward AI across multiple dimensions: they were 8-9 percentage points more likely to see AI as beneficial to themselves and society, and 8-10 percentage points less likely to view it as a threat requiring government restrictions.

Figure 1: Perceived AI threat and support for social policies

Figure: Haslberger, M., Gingrich, J., & Bhatia, J. (2025)

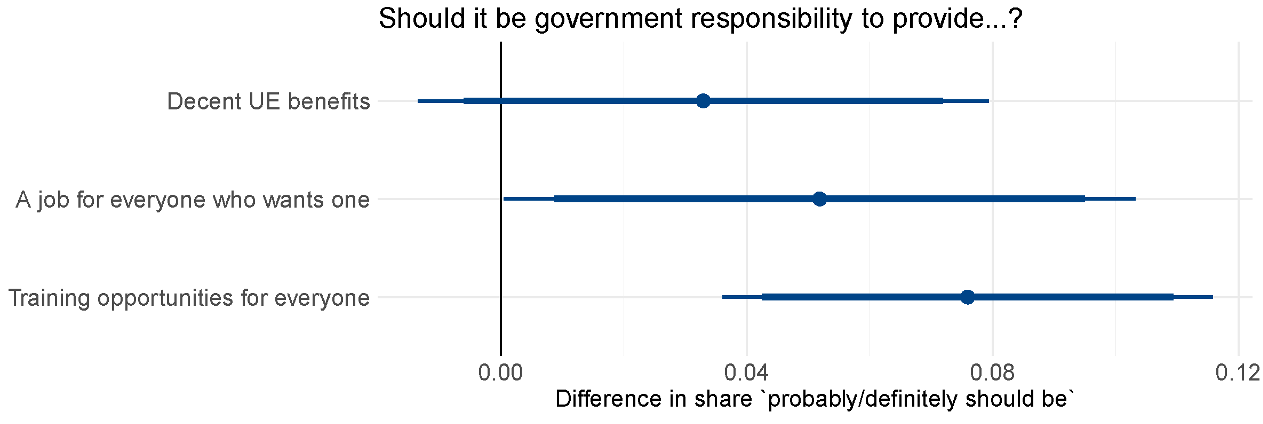

Interestingly, despite not feeling personally threatened, Figure 2 shows that treated respondents expressed significantly stronger support for activating social policies – particularly government-provided retraining opportunities (nearly 8 percentage points higher) and job guarantees (about 5 percentage points higher). This pattern contradicts the risk-insurance framework: if people don’t feel at risk themselves, why support expensive policies designed to help others adapt to technological change?

Figure 2: Effect of AI exposure on social policy preferences

Figure: Haslberger, M., Gingrich, J., & Bhatia, J. (2025)

Sociotropic Concerns: Worrying About Others

We argue this reflects sociotropic preferences – people supporting policies not for personal benefit but out of concern for others who might be negatively affected. Previous research shows that this requires beneficiaries to be seen as deserving. Several factors make this likely in the case of losers from AI:

First, compared to more gradual automation processes, the speed and scope of AI’s advance makes it harder to blame potential losers for failing to adapt. Second, unlike previous automation waves that clearly targeted blue-collar routine jobs, who wins and loses from generative AI is less obvious. This rapid change and lingering uncertainty makes it likely that losers are seen as deserving of support.

Additionally, early adopters (like our ChatGPT-using sample) may think themselves ahead of the curve, confident they’ll be among the winners even if others fall behind. This creates space for generous policy preferences toward those less fortunate.

Gender and Occupational Differences

Interestingly, we found significant gender differences. Women in the control group were more afraid than men to lose their job to someone with better technology skills, while in the treatment group the opposite was true. Consequently, the sociotropic effect on social policy preferences was primarily driven by men. Treated men were significantly more supportive of unemployment benefits relative to women, again reversing the control group pattern, and they were the main drivers of the effect on support for training policies. On the other hand, occupational differences were less pronounced than expected. Despite white-collar professionals being arguably most exposed to generative AI’s capabilities, we found no systematic differences in how AI exposure affected their risk perceptions or policy preferences compared to other workers.

A Window of Opportunity?

Our findings suggest a (potentially fleeting) window of opportunity for progressive social policy. Currently, a sense that negatively affected individuals are not personally at fault and uncertainty about AI’s distributional consequences create space for broad support for activating policies like retraining programs, even among people who expect to benefit from AI.

However, this window may not stay open long. As AI capabilities expand and its disruptive effects become more tangible, the self-interested reasoning predicted by the risk-insurance framework may reassert itself. Once people clearly identify themselves as winners or losers, their policy preferences will likely shift accordingly. The role of firms will be critical. If companies prioritize worker-complementing applications of AI rather than pure substitution – especially for junior roles – this could prevent the return to zero-sum thinking about technological change.

Beyond Narrow Self-Interest

Our study challenges the assumption that people’s responses to technological change are primarily driven by narrow self-interest. At least in AI’s early stages, exposure appears to activate broader considerations about fairness and societal consequences. The current moment of uncertainty paradoxically enables more generous attitudes toward those who might be harmed.

For policymakers, this suggests an opportunity to advance pre-emptive investment in human capital and adaptation. Rather than waiting for disruption to materialize, governments could leverage current goodwill to establish robust frameworks for helping workers adapt to the AI economy.

Will they seize this opportunity before the window closes?

Image: unsplash.com