Ask around in liberal circles and you’ll hear a familiar refrain: “Who would ever date a supporter of the radical right?” The assumption runs deep in many quarters that backing a radical-right party is the ultimate social dealbreaker, the kind of confession that would leave your dating profile permanently swiped left into oblivion. As far as many are concerned, supporters of parties like AfD, VOX or Reform UK are destined for social exile. A long-standing principle in liberal countries is that the social tolerance of intolerance is bad and, in order to protect society from the contagion of unpalatable and extreme political views, we socially penalise those who break away from the values and norms we value as important in tolerant societies. But the contemporary reality is far more uncomfortable.

The myth of the un-dateable voter

The prevailing wisdom has been that being associated with the radical right comes with a powerful social stigma — something so “beyond the pale,” that it would kill your social prospects. As a result of these social costs, people were less inclined to reveal these views publicly – if people know I hate immigrants then I’d be blocked from the from the group chat, best I keep these views to myself.

The idea that we, as a society, collectively uphold liberalism by socially sanctioning those with intolerant views is a comforting narrative, especially for those who view their political beliefs as a mark of moral decency, and who assume that society at large shares their disdain for illiberal, nativist or even outright explicitly xenophobic views.

The radical right has become increasing normalised over time. In fact, the evidence we find shows that radical right voters are not, in practice, shunned from the dating market in any meaningful way. If anything, they’re often treated just like anyone else. Why? Because in times of polarization – when centre-right voters and centre-left voters hold such negative views of each other – voters are far more inclined to accommodate those on the extremes instead of crossing the political aisle.

Normalisation, not ostracism – the tinder test of democratic norms

To test whether voting for the radical right comes with social costs and a lower chance of finding a date, we conducted a behavioural experiment with over 2,000 participants from Britain and Spain. Participants – men and women, straight and LGBTQ – were asked to swipe on over 20,000 AI-generated dating profiles that varied randomly in looks, ethnicity, occupation, education, interests, and most crucially, political affiliation.

Examples of dating profiles shown to participants in the experiment

This design allowed us to test whether simply expressing support for a radical right party (Reform UK in Britain, VOX in Spain) reduced a person’s dating appeal. Are radical right voters rejected more than accepted when looking for a date?

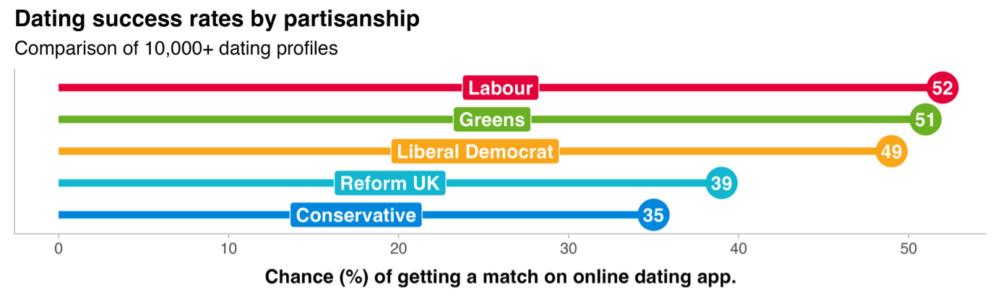

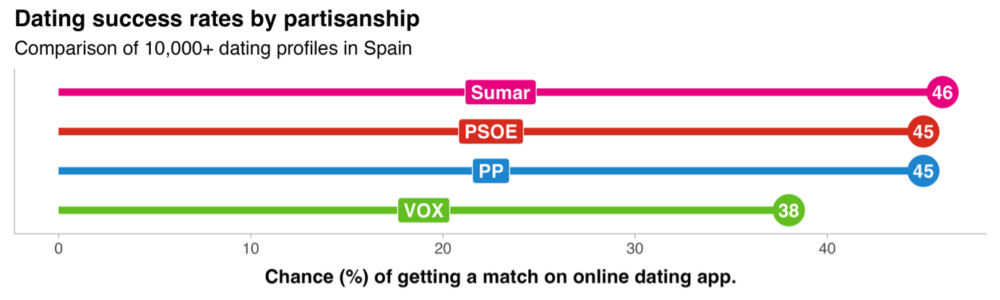

When participants swiped left or right on actual profiles, the penalty for radical right support was surprisingly weak. In Britain, radical right supporters were more likely to be chosen than Conservative supporters. In Spain, there was a penalty for radical right supporters, but only among the more left-leaning participants. Participants who vote for the centre-right in Spain preferred a radical right voter over a centre-left voter. Political difference drives the penalty rather than social stigma.

Conservative voters had the lowest chance of getting a match online, below Reform UK. Labour voters had the best chance, with similar success rates amongst the Greens and Lib Dems

In a world of ever-deepening political polarisation, it turns out that the lines that matter most aren’t between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” views — they’re between political camps. People are more likely to reject someone from the opposing ideological bloc than someone from a party with extreme views within their own camp. For many on the centre-right, the “enemy” isn’t the radical right — it’s the centre-left.

VOX voters had the lowest chance of getting a match online, below all other Spanish parties. But VOX voters were only rejected by parties on the left. Centre-right voters (PP) viewed a profile from VOX like a profile from the PP.

The real danger: the radical right as ‘just another choice’

This raises a pressing question for anyone who cares about liberal democracy. If supporters of the radical right are treated like “any other” prospective date, what does that mean for the broader struggle against intolerance? The decline of social stigma against the radical right is not an accident — it reflects a deeper shift in how political identity has hardened into rival camps. In this landscape, the willingness to date a radical right supporter isn’t about shared values or ideology — it’s about rejecting the other side at all costs.

This is dangerous. Social stigma at its best, has served as a firebreak against the mainstreaming of illiberal, exclusionary politics. When even our most personal choices — who we love, who we build families with — are no longer affected by these boundaries, we risk sliding further into a world where the radical right is normalised, accepted, and ultimately empowered.

The burden of resistance cannot fall solely on the political left. Centre-right partisans must recognise that their accommodation of the radical right is not neutral — it is enabling. By treating radical right supporters as acceptable partners, allies, or coalition members, they erode the social and political norms that uphold democratic values. The centre-right has long claimed to be a bulwark against extremism and they have served this role in in the past. Today, it faces a choice: act as the guardian of liberal democracy or become complicit in its unravelling. When it comes to forming social relations, so far, the centre-right is complicit.

So, is it really that hard to find a date when you vote radical right? The answer, unsettlingly, is no. But, for democracy’s sake, maybe it should be.

Image: Unsplash.com