Emiliano Grossman summarises recent political events in France and offers his take on Emmanuel Macron’s strategy, attempting to sketch out possible scenarios for the political landscape after the second round of parliamentary elections on July 7th.

Just minutes after the publication of the results of the European elections in France, Emmanuel Macron announced early legislative elections for the 30th of June (first round) and the 7th of July (second round). This decision came as a surprise to most stakeholders and observers and triggered a series of intense debates and negotiations in the French political arena. And yet, it is unlikely that it will solve the current crisis. In fact, it is more likely to exacerbate it.

From the preparations for the European elections to the dissolution

The European elections in France on June 9th were widely expected to be dominated by Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) party. The polls had been very favourable to the RN for a long time, while expecting Macron’s party to suffer significant losses considering the 2019 European election and the 2022 legislative elections.

In a surprising move, the government has proposed a televised debate between Jordan Bardella, head of the RN list for the European elections, and Prime Minister Gabriel Attal. This was an unprecedented event, since Gabriel Attal was not a candidate for the European Parliament. The debate drew fierce criticism from the rest of the opposition, as it placed considerable importance on Jordan Bardella, regardless of his performance.

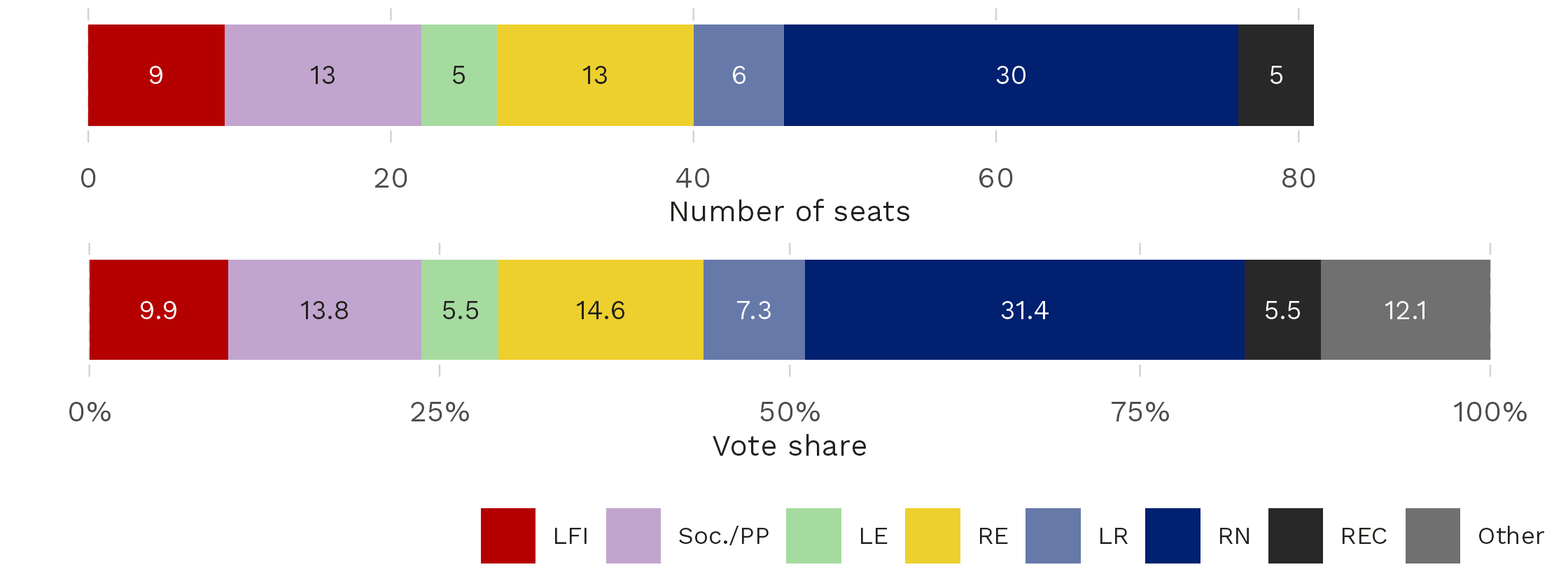

The initial results have confirmed the polls, as shown in the graph below. France uses a rather proportional electoral system for the European elections, as illustrated by the overall correspondence between votes and seats in the 81 seats that France has in the European Parliament.

Figure 1. French vote and seat allocation for the European Parliament

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Data: French Ministry of Interior

Renaissance (RE), Macron’s party, came second, securing less than half the votes of the RN. Moreover, the alliance between the Socialist Party and Place Publique (Soc./PP), with its popular leader, Raphaël Glucksmann, did almost as well as Renaissance.

While the result of an election with a low turnout (51.5%) should not be overestimated, the results are in line with general trends since the 2017 election, which had led to a profound restructuring of the French party system, as analysed by Gougou and Persico (2017). This process is far from over: it has probably ushered in a period of much greater electoral volatility. The two parties that dominated the political life of the 5th Republic, the Socialist Party and the Gaullist Party, whose current heir is Les Républicains (LR), seem very weakened today, or even threatened with extinction. Emmauel Macron’s party had achieved excellent results in the 2017 legislative elections, benefiting from the demobilisation of conservative and far-left voters. After obtaining 28% of the vote in the first round, it won 53% of the seats in the second round. The presidential camp was unable to repeat this success in 2022, winning just 38.5% of the seats.

This does not mean, however, that the government was unable to govern. French governments do not need an investiture vote: they just have to survive a vote of confidence when one is held. This weakening of the government has resulted in regular votes of confidence. The vast majority of these have been in response to government initiatives based on Article 49.3 of the Constitution. This is a powerful tool at the disposal of weak executives: a bill is deemed to have been passed unless a government is voted out of office. It is partly thanks to this procedure that Elisabeth Borne, Macron’s Prime Minister until January 2024, has managed to push through several dozen bills. This includes the highly controversial pension reform or a bill limiting the rights of immigrants.

Emmanuel Macron’s risky gamble

The motives behind Macron’s call for early elections are not entirely clear. One explanation advanced by his entourage relates to the difficulty of governing with a relative majority. This is arguable, as previously mentioned. Another explanation is the need to respond to the message sent out by voters in the European elections. Again, this argument is not entirely credible. In 2014, the outgoing Socialists came 3rd with less than 14% of the vote without any tangible consequences for the Socialist government.

There seems to be a third, more convincing reason. While Marine Le Pen is increasingly seen as the most credible candidate for the 2027 presidential election, this early election could force her party to begin taking responsibility before then. The “cost of government”, i.e. the necessary voter fatigue that incumbents tend to suffer over time[1], could then dent their chances of victory in 2027.

On the other hand, Macron was no doubt hoping that this initiative would unite his own supporters and force Gaullist MPs to more clearly acknowledge their support for his government. The fact that the left continues to be deeply divided could in turn have contributed to this. The very short deadline (three weeks before the election and only one week for the submission of candidatures) seemed to make negotiations between the political groupings unlikely.

Whatever the motivations, the reactions were rather unexpected. The four main left-wing parties managed to conclude an electoral agreement in just four days. Although divisions remain, the left-wing alliance could do well in the elections. Meanwhile, Eric Ciotti, the president of Les Républicains (the former Gaullist party), declared an alliance with the RN on June 11th. This led to his own exclusion from the party, later invalidated by the courts, and may have further weakened the presidential camp. Finally, the RN failed to reach an agreement with the other far-right party, Éric Zemmour’s Reconquête (REC).

And now?

In the current context, none of Macron’s favourite options seem very realistic. The presidential camp, made up of his own party and other centre-right forces, is likely to lose a large proportion of its seats, while its eventual allies in the Republicans will be fighting for their electoral survival. At the same time, the RN does not look likely to achieve an absolute majority of 289 seats, although some polls suggest it could come close. One of Macron’s preferred scenarios could therefore come true: the RN would win an absolute majority and would have to govern with little or no preparation.

The most likely scenario, given the data currently available, is that of a parliament with a relative majority for the RN, a second left-wing bloc and a small centre-right bloc. This is likely to make the Prime Minister’s task very difficult and votes of confidence are likely to be lost, leading to levels of governmental instability worthy of the 4th Republic–which had 24 governments in 12 years. A “technical”, i.e. non-partisan, government could appear to be a desirable option in these circumstances.

In any case, it is unlikely that the dangerous gamble of dissolution will significantly reduce Marine Le Pen’s chances of victory in 2027. In the meantime, it will have created a great deal of uncertainty and increased tensions within French society. Political scientists know that they can–at best–interrogate the past, but are generally poor when they try to predict the future. Clearly, Macron is no better, but the consequences of his actions are far more important.

[1] See Emiliano Grossman and Isabelle Guinaudeau, “The Cost of Ruling above everything else: explaining party popularity in France” in Timothy Hellwig et Mathew Singer (Eds.), Economics and Politics revisited: Executive Approval and the New Calculus of Support, New York, Oxford University Press, 2023, p. 80-107.

Picture: Flickr